www.cineuropa.org

www.cineuropa.org

Mantas had returned to Mariupol. In 2016, he made a film there, Mariupolis. It screened in Berlin, and shone a light on a war happening far away. One almost had to explain where Mariupol was to clarify the nature of those atrocious, yet also "beautiful" and heartbreaking images. A city in the South-East of Ukraine, in the Priazovia region, it is situated on the Northern shores of the Azov Sea, near the mouth of the river Kal'mius. Traditionally Russian-speaking, it has a population equally split between Ukrainians and Russians. Mantas had brought his camera among those people. And when one lazily asks what purpose cinema may still serve, there can only be one answer: to understand the world, and what the people living in it are doing.

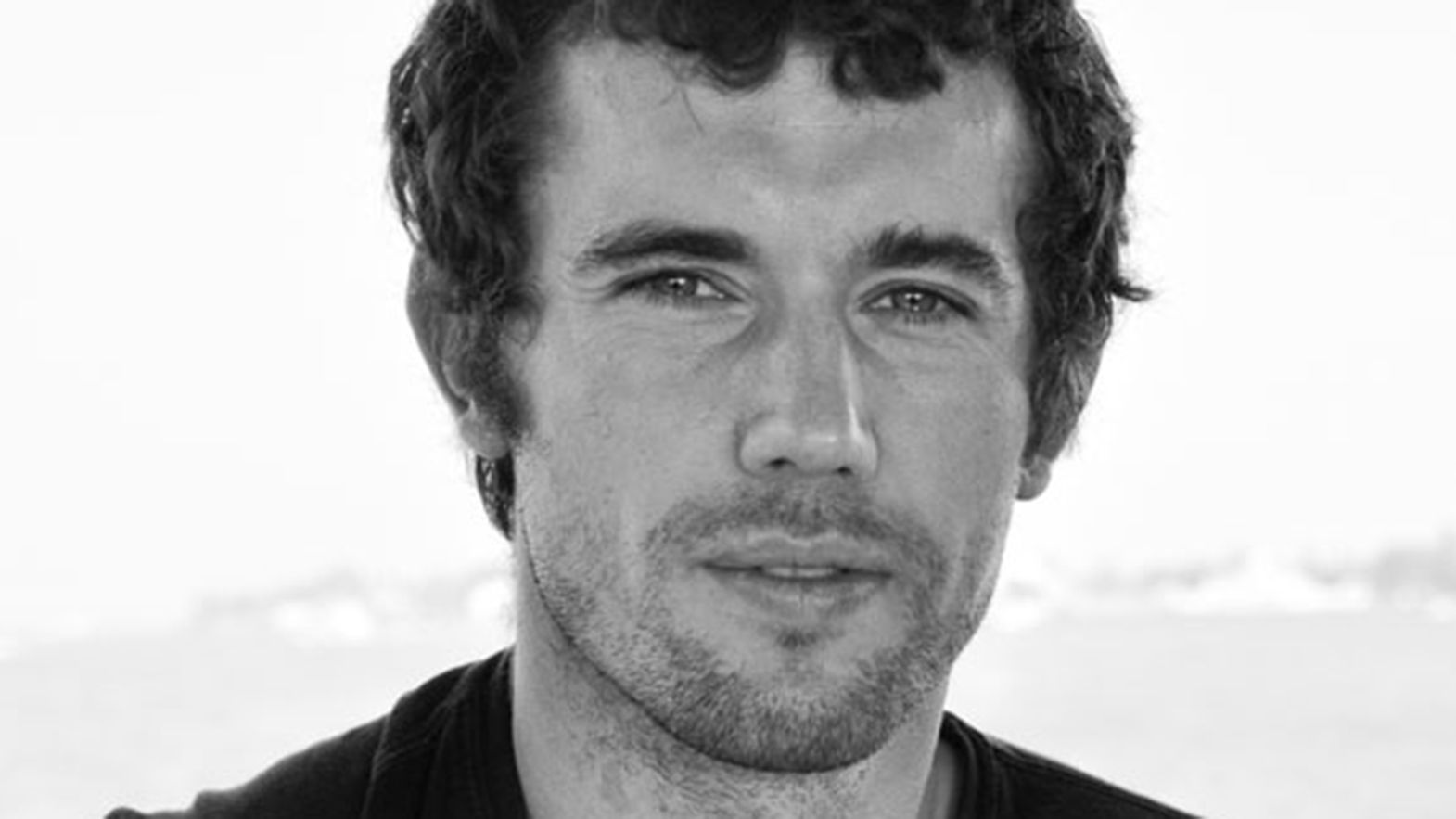

We knew there was a war. Living a privileged life far away from the border, we thought it was a distant one. As usual, it was "their" problem. As though we were safe from history, which only kills "the others". Mantas was not a militant director. Or rather: his militancy was the poetry of direct testimony. His gaze picked up on layers of a reality that was otherwise invisible in cinema. His images are profound, with a vertigo-inducing visionary strength. Over the years, I ran into Mantas many times. In Nyon, in Vilnius, around the world, at festivals. Sometimes he was with Uljana Kim, his friend and producer. Mantas was not an easy person, or perhaps he had a healthy distrust vis-à-vis a world that dealt with cinema, and yet did not or could not see a lot of things. So he stood there, listening, perhaps trying to understand which elements of his work were of interest to cinephiles who already saw many (too many?) images.

In 2019, as part of the 34th International Critics' Week in Venice, we invited Parthenon (also known as Parthenonas), his first "fiction" film, which actually came from the bowels of the world: Athens on fire, the tragedy of refugees, the shadow of Odessa, and the symbol of Western society, the Parthenon, standing there powerless. It was an intoxicatingly beautiful piece of work, running like a river. After we insisted countless times, he agreed to send us a synopsis of sorts, to explain his film with a few words. We were struck by the lyricism of the description. Here it is: " 'I will not cry out of regret, but fear that I may not be able to satisfy my passion', she said. The day it snowed in Istanbul, Garip killed Mahdi. Garip and Sofia were madly in love once. This happened in Odessa, but it all began when the sands of the Sahara covered the city of Athens. Whose memory was it? Or whose memory will it be?". So, who will this touching memory of Mantas belong to?

When the time finally came to introduce the film in Venice, it seemed like he wanted to be anywhere but on the Lido. The film was enthusiastically embraced by a passionate group of cinephiles, but given its subsequent lack of visibility, one suspects he wasn't interested in that kind of conversation about his work. He surprised me with a question he asked as we were studying each other, as though we'd met for the very first time: "Did you actually like my film?" That apparent insecurity surprised us, but within it was a genuine desire to meet other people and have sensible conversations.

In Locarno, he'd been a guest of the First Look program with the project for Parthenon, then called Stasis, but it always pained him to have to explain his ideas, which came from the encounter with places and people. The language of pitching almost bothered him. His cinema transcended the real and drew upon the most remote regions of poetry. How could you recount or explain that? And above all, why? Mere days ago, I'd been chatting with Markus Duffner about the impact Mantas' work had had on cinema in recent years, as we were fully aware of his greatness.

Mantas had gone back to Mariupol. He wanted to see the city again, understand what was going on. A missile hit his car and ended his existence. He was born in 1976. Apparently, he died with a camera in his hand.

------

UPDATED 11 | 4 | 22

The death of Mantas Kvedaravicius echoed like a sinister note in a rising tide of horror. We're devastated by the passing of a young filmmaker who had gained attention via the singularity of his vision, which still isn't (and never will be) fully understood. Right after the Locarno Film Festival's tribute started getting shared online, within hours we were contacted by friends of Mantas and his family. Sadly, reality can be more horrifying than our imagination. Mantas' death did not occur as initially reported. He was stopped, arrested and killed on the spot by Russian soldiers - a veritable execution. His wife, Hanna Bilobrova, who had lost contact with him on March 26, was trying to bring the body back to Lithuania, avoiding the various Russian roadblocks. She found her husband's body on April 1, on the street in Mariupol. The signs on the body were unmistakable. The story wasn't shared immediately, allowing Hanna to leave Mariupol with Mantas' body and the footage he had shot. She then recounted the experience to Lithuanian journalist Vidmantas Balkūnas. By the time the story was finally clear, Hanna was already on the way back home, and on April 5 she crossed the border from Russia into Latvia. A few days later, the funeral was held, with friends and family in attendance. And we reach out to them with our heartfelt thanks, for keeping us posted, day by day. Mantas has been laid to rest in Biržai, in Northern Lithuania.

Giona A. Nazzaro