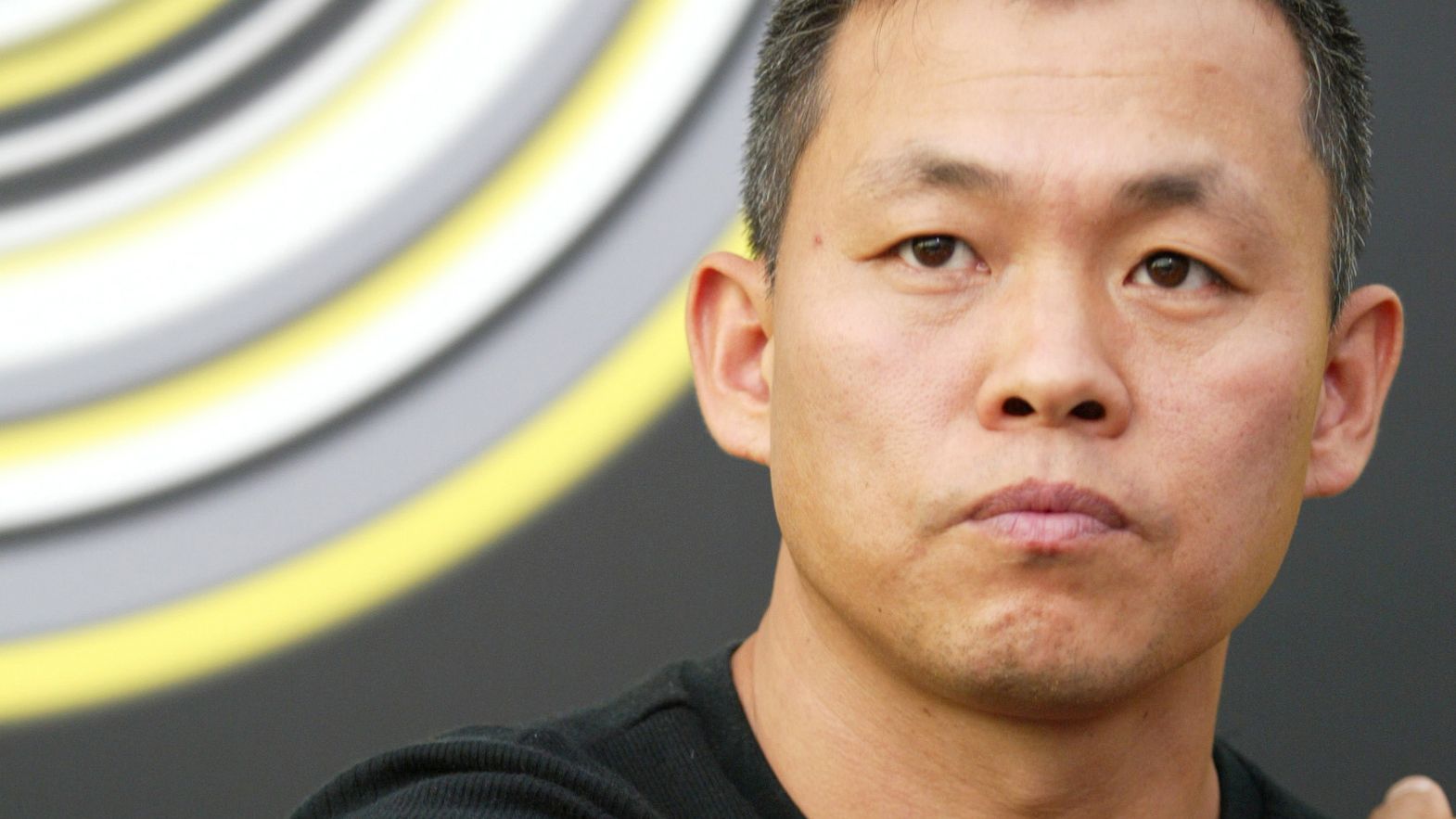

Kim Ki-Duk, Locarno 2003

Kim Ki-Duk, Locarno 2003

For a long time Kim Ki-duk was South Korean cinema. He first captured global attention at Venice with his fourth film, The Island, which underscored his highly personal vision of the world and of the power relations between humankind and nature. It also highlighted his taste for profound, uncompromising, lyrical cruelty, the sign of a world that does not answer to human desires and expectations. One woman in the audience in Venice was so overpowered by Kim’s explicit images that she fainted — a response which some might see as tantamount to a standing ovation.

Yet, despite his demoniacal reputation, Kim was a far more complex and refined filmmaker than the cruder extremes of his cinema might have suggested thus far. Which is why, when Kim Ki-duk arrived in Locarno in 2003 with Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring, after two starkly contrasting films such as Bad Guy and The Coast Guard, the Festival audience discovered an auteur capable of modulating his gaze with extraordinary elegance. As the high point of a unique auteur journey, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring is probably the supreme filmic expression of the director’s inner world, convincingly articulated in a way which made the portrayal of his demons more gentle than before. Some of his earlier coarseness came back in the films that immediately followed, but at the same time they also underlined the increasing complexity of his cinema. Samaritan Girl and 3-Iron in particular were the hallmarks of an auteur director at the top of his game.

Kim’s prolific output was legendary, but its overall quality was inevitably affected by the constant stream of movies he directed. In that context, The Bow clearly showed that quality could not keep pace with quantity. And then came Dream. On the set of the film, the female lead Lee Na-young very nearly choked to death when safety equipment failed during a hanging scene. Kim Ki-duk was distraught, disappearing from public view for a period.

Three years later in Cannes he returned, changed almost beyond recognition, with the documentary Arirang. Named after a Korean folk song, this was an unsparing account of the director’s own bout of deep depression, playing brilliantly and daringly with his own image, and boldly treading the confines between fiction and autofiction. After Arirang, Kim returned to making films with undiminished energy. In 2012 he won the Golden Lion at Venice for Pietà. Receiving the award from Michael Mann, Kim said thank you by singing Arirang.

The last years of Kim’s life were stained by the multiple accusations of sexual abuse, physical assault and predatory behavior that were made against him. Three women, all actors, claimed the director had taken advantage of his position to obtain sexual favors. He faced the grievous accusation of having committed rape together with his preferred actor, Cho Jae-hyun, and was fined five million won over charges of physical assault involving an actress on set. Kim gave up all his public positions. The notoriety of these heinous episodes casts a dark shadow over the creative pathway of a director who made some of the most acclaimed South Korean films of recent years. It is a grim epilogue to his story.

Giona A. Nazzaro