A Doctors-Prescribed Purple Flower

By Salvador Amores

Salvador Amores is a critic, programmer and occasional filmmaker based in Mexico City. His writing has appeared in MUBI, Variety, FICUNAM and Correspondencias. He worked as an assistant programmer for FICUNAM and has curated film series for the Institut Français d’Amerique Latine and the Black Canvas Film Festival.

I’ve struggled with what this text should be about for most of the past month. I had been reticent when it came to reading columns in which a writer speaks their mind about the lockdown experience only to later speculate on what they believe will be its implications in the cultural sphere, so when I was commissioned a text that linked my festival experience with the current world situation, I was worried. Perhaps prematurely, I emailed saying I could write a more traditionally structured text around the films of Axelle Ropert, for I had discovered her wonderful 40-minute comedy Étoile violette (2004). They said yes, so I started outlining some of what I found exhilarating about these films. But the days were going by and I wasn’t arriving at anything that either felt honest to my state of mind or made justice to the uncomplicated beauty and gentleness of her oeuvre. Unlike M. Night Shyamalan, who recently posted on Twitter he had storyboarded over 400 scenes of his new film during the lockdown, I’ve had a hard time setting my mind straight while coping with the uncertainties of unemployment, the ever-increasing dampening of the Mexican economy, or my rushed moving out of Mexico City and into a nearby town that’s not yet struck by gentrification. Thankfully, sometime around the course of these weeks I either gave up or simply realized Locarno’s initial mandate of producing a text inclined towards the private was correct all along – perhaps Christopher, in charge of the project, too had felt it impossible and contradictory to turn in one of those impersonal and pretendedly objective texts about film form in times like these. So, in an attempt to untie some of the threads the pandemic had tightly entangled in my brain, I reached out for the other smaller and cheerier thoughts I had glimpsed from time to time during what’s now been a five-month lockdown; maybe, if I let them expand, they’d be firm enough for me to hang on to. Some ruminations about film criticism, medicine, and my mixed memories from the last summer alternate in this text with some aspects of what I love about the films of Axelle Ropert. In a way, Ropert's films, as preoccupied as they are with feeling, demanded from me something in accordance.

An editor-in-chief for the mythical La lettre du cinéma — a journal that championed such forgotten French auteurs as Jean-Claude Guiguet and Danièle Dubroux and which also spent many of its pages attempting to unravel the increasingly complex continuities of the nouvelle vague (a subject put aside by the Cahiers of that time) through analysis of the late films of Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette — Axelle Ropert has only released four films since 2004. She is normally associated with a rather particular clique of heterogeneous French filmmakers who collaborate from time to time in each other’s work and who showcase an ample knowledge of the history of cinema through the radiant transparence of their films: Serge Bozon, Pierre Léon, Jean-Charles Fitoussi, Jean-Paul Civeyrac, Vincent Dieutre, et cetera. Ropert’s films, mostly comedies, are, unlike those of most of her peers, classical in the best sense of the term. The fragmentary, elliptical trickery that envelops the majority of contemporary storytelling in cinema is traded for a love of novelistic continuity and a clear outlining of character types that links these films with the ample tradition of the great ancient comedians. Though the way these films inhabit tradition is entirely their own, there is much of Ernst Lubitsch, of Leo McCarey, and of Blake Edwards in them. For instance, in their rejection of emotional ambiguity and its dampness, replaced instead by what one perceives as an evident delight in basking under the clear skies of unbridled — yet always lighthearted — sentiment. Leo McCarey once said, “I love when people laugh. I love when they cry, I like a story to say something, and I hope the audience feels happier leaving the theater than when it came in.” To paraphrase a certain text of Ropert, let’s be ridiculous: I’m sure Leo McCarey would have loved these four films, though his preference would almost certainly be towards Tirez la langue, mademoiselle (2013), her second feature-length work, a doctors’ melodrama.

Probably because the pandemic has emphasized the medical profession in the collective imagination in an unprecedented way, as I browse social media and come upon the wave of journalists who are eager to identify a McLuhanian change of paradigm happening right in front of their very eyes, I think of doctors. I have a very dear friend in Mexico City who is a doctor and also happens to write about film. Many of the times I ran into him at a screening, he’d say he came straight from the hospital to make it on time. When I read his texts, I have the feeling he separates both occupations with a very diligent lucidity. Though I’ve never seen him work, I’m sure he doesn’t think of his patients as characters in a film, and accordingly he wouldn’t think of film as a patient of any kind. In contrast, film critics tend to have some sort of doctor complex. As they rummage through the rubble of contemporaneity, they figure that the cinema must be ill. Diagnoses made, they then prescribe a treatment based on their aesthetic or ideological concerns, with which, if followed closely, the cinema will eventually get better. As for film festivals, they tend to regard the films as if a body (the cinema’s) was laid upon a big table, perceiving themselves as ready to perform an autopsy. The ambition of speaking generally about a “state” of things is perhaps inherent to the temperament of an art critic, but in this time of deep reformulations I ask myself whether this mindset stills speaks — to us, to readers, and better yet, to the cinema itself — in any way. These days I tend to diverge from my most immediate concerns daydreaming about what would happen if we actually used the pandemic and our new worldwide fixation with medicine to our advantage and started to think not of new viruses that are either metaphorically or literally corroding the cinema, but in the very essence of our roles as film critics and the relations we establish with and around our object of desire…

Could one speak of medical realism? Tirez la langue, mademoiselle tells the deceptively simple story of two doctors who are also loving brothers and end up falling for the same woman, their patient’s mother. What will be offered to our eyesight and our hearing though is not a clinical analysis of the characters through the procedures of an over-rigorous formal program, but rather a loving, candid, soft gaze set upon the surface of their emotional struggles. That is to say we are far from Flaubert and close to John Ford’s Doctor Bull, as Ropert’s film aligns itself into a very particular type of medical realism enabled by cinema’s virtues, one very distant from that permitted by 19th century literary conventions. Ropert wears her forebearers on her sleeve and rejoices in shaking up tones in a way that strikes the viewer, again, in a McCareyian fashion: the doctors’ story is as prone to laughter as it is to tears. Likewise, the great tradition Ropert admires lives on in her specific way of snubbing psychology and naturalism through a deep confidence in tropes and their surfaces: she makes of the characters little more than what their duties oblige them to be. They are doctors, and brothers, nothing more; a mechanism that allows the film to move us by way of its other qualities. Ropert is not working mise en scène from the precise, almost mathematical obsessions of Bozon or Emmanuel Mouret, so these virtues are instead crystallized in the unfolding of the narrative, the witty dialogues, the gestures with which the actors convey them; and, ultimately, the pleasure derived from the conjunction of both.

To sum things up, Boris Pizarnik (Cédric Kahn), the coarse brother, falls in love with Judith Durance (Louise Bourgoin), the mother of their diabetic girl patient, quietly, as is his way, after Judith makes some advances on him. Then Dimitri Pizarnik (Laurent Stocker), the timid figure, falls in love with her too, out of his own advances, when she seems interested and understanding over his alcoholic condition. Dimitri, as extrovert as he is, tells Boris he is in love with Judith when Boris is already well on his way through his own romantic enterprise, and Boris chooses to remain quiet about it. As expected, Judith and Boris are eventually caught red-handed by Dimitri. The rupture begins and the two doctors end up splitting. Eventually Judith goes back to her ex-husband and Boris, heartbroken, chases after Dimitri in what is the film’s most striking scene, a dim-lit embrace between two brothers who had been all along, we now know it, caring for each other. It is evident Ropert’s universe is a moral one, but putting aside that critical cliché, the doctors’ predicament, made explicit through the choice of their profession, brings forward one of the keys to Ropert’s poetics, what all through her oeuvre regulates both the stories and the formal procedures through which they are conveyed: the notion of taking care.

Just as one brother was fundamentally a patient to the other, Judith exists as a character only in relation to her condition as a mother who’s taking care of her daughter, little sick Alice, and in a similar way Simon Wolberg (François Damiens), in La famille Wolberg (2009), a father and a mayor at once, is but a caretaker, for his town and his family. In Ropert’s films hardly a single egotistical character exists, even if at times these characters’ profound caring is hidden away under the shroud of confidentiality. The secret, something very dear to her cinematic constellation and shared by all her characters, is such because its bearers are mindful not to hurt somebody else by revealing it. In her last film, La prunelle de mes yeux (2016), this system of caring and secrecy is what fuels the narrative device, as it becomes even more complex and reaches new heights of dynamism through the intricacy of the scénario. In the small universe of a Parisian arrondissement Léandro Papagika (Antonin Fresson) takes care of his brother Théo (Bastien Bouillon) by not telling him how bad he is at playing the bouzuki; neighbor Marina (Chloé Astor) takes care of her sister Élise (Mélanie Bernier) because she is blind; blind Élise takes care of Marina’s cocaine addiction; and Théo, head over heels in love with Élise and supposedly struck by blindness too, takes care of her by not revealing the secret of having made up a terrible illness to approach her in the first place. Just as how the characters hide aspects of themselves to their loved ones, so does Ropert’s mise en scène caringly hide from our view a portion of their hearts, only to be revealed subtly at the exact, inevitable and glorious moment when all emotion collides. Such grand instants alternate gracefully with the more apparently insignificant situations they are mostly made up of — Ropert has a predilection for showing her characters at work, as well as going to or coming back from it. And just as her adherence to “classical” storytelling is less of a reactionary opposition to “radicalism” than a modest way for her to provide the care her characters and their inner turmoil secretly need, the humble questions her films tend to pose are far from the big statements so dear to current cinema. But unassuming is, of course, far from unimportant: what these films are after is the queries of the heart — what could possibly be larger than that?

Whether films are going to change; whether film festivals will keep existing or streaming platforms will replace projections; whether hoarding films in a hard drive can in any way be called cinephilia; and whether all these issues announce the ever-growing and perhaps irreversible museumification of the cinema that will complete its already-undergoing transformation into a consumer good incapable of any agency over our vital experiences; as urgent as these questions are, they cannot begin to be addressed until we turn upon our steps and reassess the drive that led us toward asking them in the first place. What is at stake when one speaks of a critic’s duty? I think of a moment in that film when newly-arrived Max Fusetti, Judith's ex-husband, accuses Boris of regarding others as medical cases; of when Annabelle, the brothers’ secretary, confronts him for having fallen in love with a patient. An old cliché of a question arises: how does one separate duty and love? Ultimately, shouldn’t a medic’s obligation be indivisible with love, with caring? And how exactly is this all relevant to diagnostic-oriented film criticism? As to our times, what could a film critic grasp from the deambulatory death that has not only stopped us in our tracks but, at its worst, struck our loved ones and made us, perhaps more than ever before, aware of our bodies’ own fragility? If we are so readily able to act as doctors, the medical analogy should perhaps be taken even further. To acknowledge cinema’s own condition as a perishable organism. Whether a film could have a cold, a fever, stop breathing, and whether it could even die too. I think of Danièle Huillet’s skepticism towards film preservation; of Godard’s idea of cinema having, like a human being, a life of 80 or 90 years at most. Perhaps once we accept the transiency of the film medium we will for once be able to begin approaching those works we love with the affection and caring they need, the ones we would dedicate a loved one for as long as they stand among us. To stop diagnosing and start caring. I draw on a lockdown read, the ending stanza of Robert Creeley’s Peace: Oh love, oh rocks,/ of time, oh ashes I/ left in the bucket,–/ care, care, care, care.

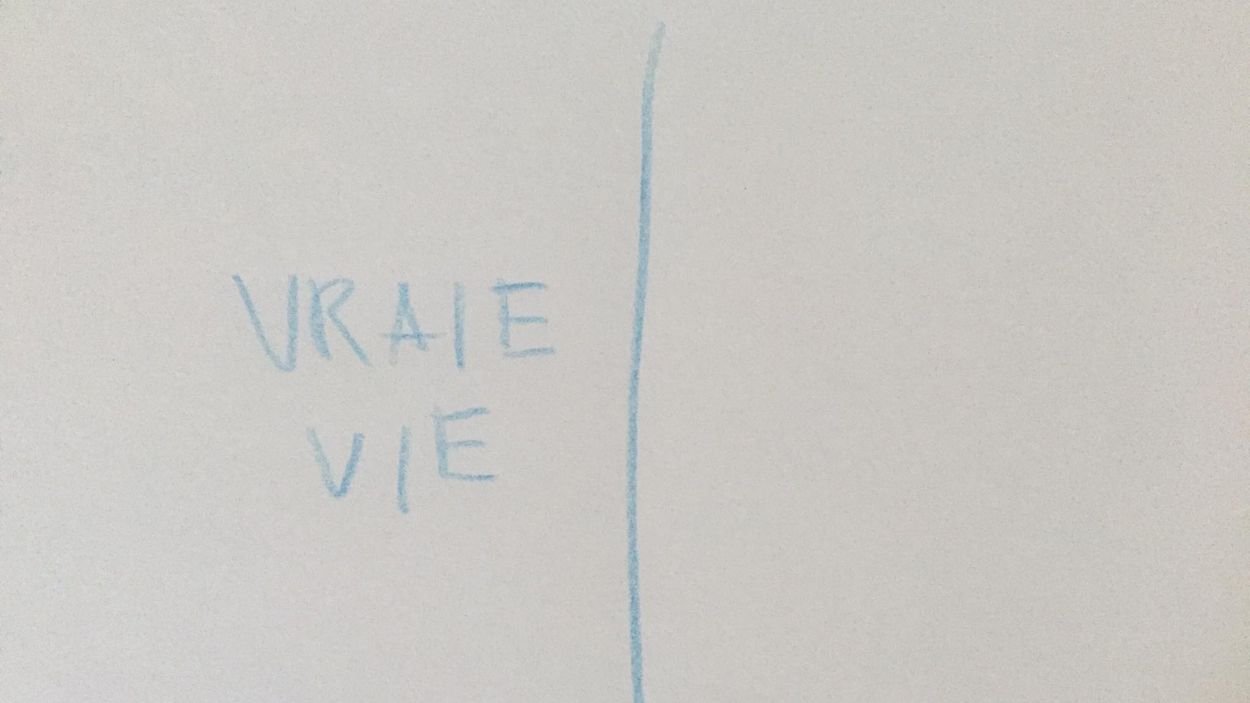

Je t’aime, je t’aime, je t’aime, je t’aime, declares Théo to Élise in the very last frames of La prunelle de mes yeux. Happy endings in these films occur only after going through a long and bumpy road, an apprentissage we’ve practically lived along with the characters, for the gentleness of the films’ unfolding has made us care enough about them. Ropert’s classicism regards change very highly, and most of her characters have undergone it by the end of their journeys. As untraceable as these transformations are, Alexandre, from La famille Wolberg, may provide us a clue towards their general understanding. Brother to Marianne (Valérie Benguigui), Simon’s wife, Alexandre has come to visit the family home with plans to stay in town until Delphine’s (Léopoldine Serre) 18th birthday party. A bearded bohemian, he spends the first night in a small cabinet where he will find little Benjamin (Valentin Vigourt) visiting early in the morning. After Benjamin tells him his father said bohemians weren’t on the right side of life, he asks Alexandre what exactly was this right side. The bohemian gets up from bed, grabs a chalk and draws in the door threshold a line separating

to its opposite, which the camera doesn’t allow us to see. Il y a des gens qui sont dans la vie, et ceux qui ne sont pas dans la vie. Le plus amusant c'est pas d’être d'un côté ou de l'autre, mais de passer d'un côté à l'autre, says Alexandre, as he gets up from the floor and both jump repeatedly from one side of the line to the other.

The vraie vie is arguably all that Étoile violette circles around. This first film tells, in a much more openly comedic manner than all of Ropert’s following films, the story of a shy tailor (Bozon) who enrolls in night school for a literature class on “Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s solitude”. The professor, monsieur Étienne, a rather pretentious bald man with a very romantically clichéd view on an array of typical philosophical subjects, makes his all-adult class observe the night stars, gives them readings to take home and has them rehearse with each other re-enactments of Rousseau’s meetings with both a stranger as well as Denise Diderot, all to — we will know it by the end — make them overcome their own loneliness. The tailor, when not in school, spends his hours listening to the radio and daydreaming while working on a blazer. In what appears to be an illustration of one of these dreams, the tailor meets Jean-Jacques Rousseau himself (Lou Castel) in the countryside. As they stroll through the woods, they talk society, women, and Rousseau’s latest pursuit: a purple flower that only blossoms at night when no one is looking; the purple star. Back at school, in the last class, after a Straubian rehearsal between Rousseau and Diderot where the tailor plays Rousseau, Monsieur Étienne scolds him for a bad impersonation and for not having understood what the course was about at all. Je suis ici pour vous aider à vivre ensemble, et pas pour autre chose. Oui, ensemble. Vous avec vous. Vous avec vous. Vous avec vous! C'est ici et maintenant qu'il faut vivre. Dans la vraie vie, que ça vous plaise ou non, et ensemble! Change, in Ropert’s films, always involves contact with other people. If Alexandre, the bohemian, was à côté de la vie, like a timid spectator in a football game, it was mostly because he was a loner. The caring and the secrecy these sentimental educations entail amount to one thing only: putting one’s solitude in perspective. In Étoile violette, once class is dismissed, we’ll see Monsieur Étienne looking through the window, at the school’s entrance, rejoicing upon the sight of his fulfilled purpose. As he holds the mythical purple flower in his hands, all the students are talking to each other. The accountant with the warehouseman, the secretary with the receptionist, the tailor with the nurse. If awkwardly, they’re making contact, overcoming solitude: entering the vraie vie.

A dreadfully similar feeling of having traversed a threshold gets a hold of one’s own frame upon exiting a theater after a screening. Nostalgia aside, that’s what I miss the most of life before the pandemic. Passing from one ‘side’ to the other as you entered and left a film projection.

A year ago I was in Locarno. It was the first time I’d been in Europe. When I mentioned that to some new and old European friends they reacted by saying it was a rather strange place for a first time in the continent. They didn’t elaborate further, so I never really understood why. While it all certainly looked very clean and polished and didn’t have the murkiness of some other milieus I had seen in the European films I love, it did have some of their other traits. People weren’t very keen on giving hugs, passersby were rather coarse when asked for directions, and most locals could get very upset upon realizing you weren’t understanding a thing they were saying. What’s more, I even recall walking up a street with Ka Ki, from Hong Kong, when a white man passed by us yelling “konichiwa”. While all these certainly make up comical stories on some of the more rancid aspects of Western Europe I enjoy telling my friends back home, at this given moment in time I choose to privilege some other memories from that trip. I think, for instance, of a joyful disagreement with Linda over a film by Pasolini, of being locked in some ancient college with Wilfred for hours during a pouring rain. Of that time I talked to Sadia about anxiety disorders, of when I ran into Nathan who, like me, had showed up at the wrong theater for a Bill Gunn screening and ending up walking together into what was, to our surprise, a tribute to Enrico Ghezzi; or finally meeting up with Luciano, whom I had, for a very long time, known only virtually from a cinephile website. I am often visited too by the thought of having perhaps taken for granted some of the smaller gestures my memory strangely holds on to: shaking the hand of Jean-Claude, a filmmaker I admire deeply, kissing the cheek of my friend James, hugging Lucie goodbye and even sitting next to Sofie to watch a Robert Wise film. More than ever before I feel how absurd it was having traveled across an ocean to sit in the dark next to a stranger, only now I rejoice in this nonsense. It’s as if the purple flowers grew in the darkness of those small cracks between one image and another, or perhaps even in between two cinema seats occupied by people who had not met before. And after the film had ended, as we stood in that small yard outside the Rex, just as in that one haunting final scene in Étoile violette, we felt, if very briefly, that we had overcome our solitude. Jumped to the other side of the chalk line. Dans la vraie vie […] et ensemble!

In lack of a proper conclusion, one of those where a writer ties everything together through the resonance of a subtle yet grand finale; I draw on a lockdown listen. I discovered this tune thanks to Serge Bozon’s turntables a couple of years ago in an old Mexico City apartment. It was also through him that I first heard of Ropert’s films. As months have been coming and going, I’ve felt increasingly lured into the lighthearted joy the singer utters them with and naturally to what the very words convey. Reach for the sky, touch your star/ And then you find your dream, find your dream/ 'Cause dreamin' alone, it's a shame indeed/ But if you got love that's all you need. I’ve self-prescribed a daily listen of this record, for it gives off a similar emotion to that of watching a film by Axelle Ropert – Didn’t the ending of La prunelle de mes yeux tell us, like The Tams, to be young, be foolish, and be happy?

As I ponder on diagnoses and cinema; as I try to unravel the films of Axelle Ropert; as I remember my trip to Switzerland and yearn for film screenings, one phrase by songwriters Ray Whitley and J.R. Cobb keeps coming to my mind – it seems to affirm with a clarity I could never hope to achieve what all these threads had somehow suggested: “dreaming alone is a shame indeed”.