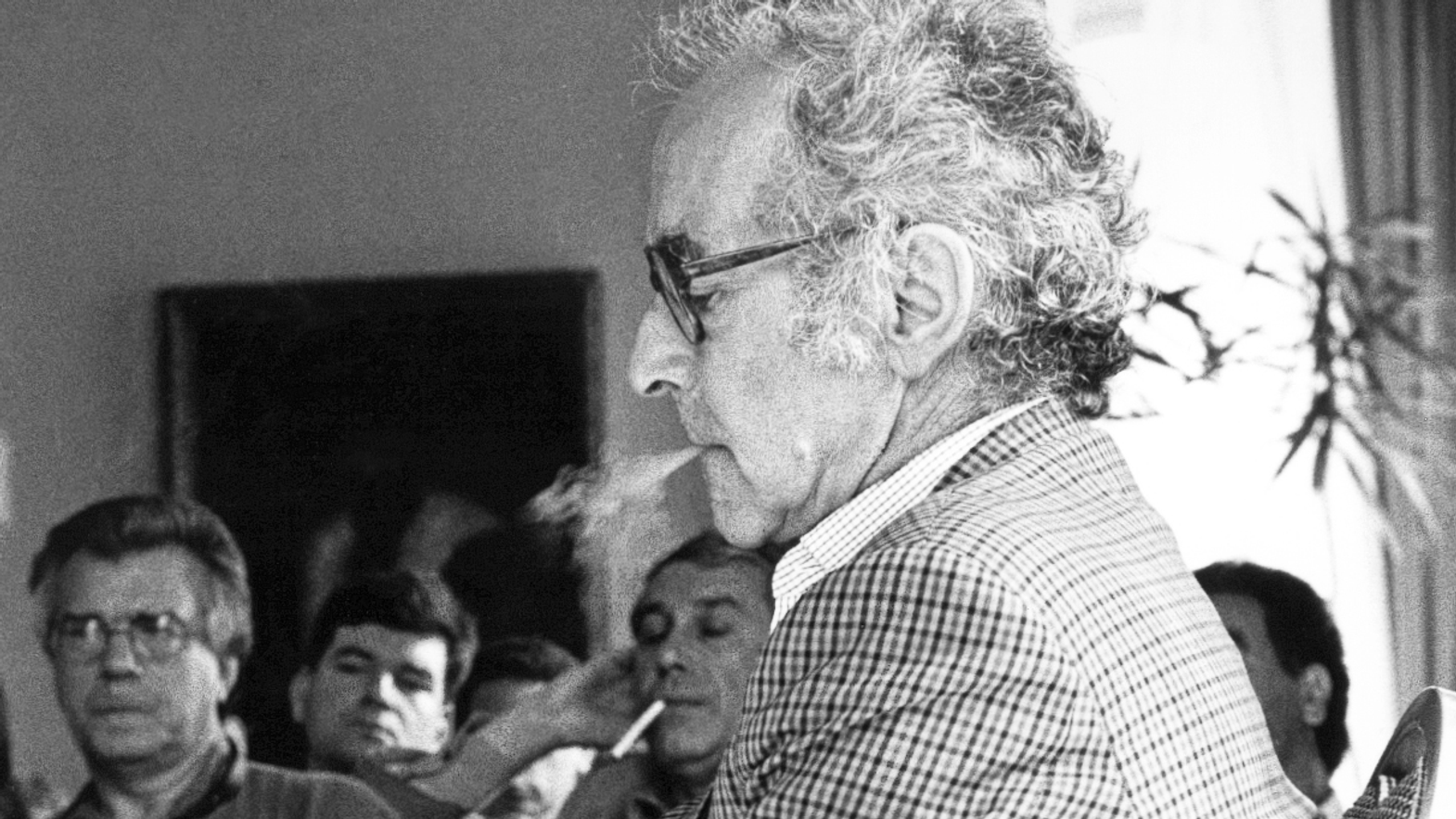

Watch the Conversation with Jean-Luc Godard, Pardo d'onore 1995

Jean-Luc Godard, Locarno 1995

Jean-Luc Godard, Locarno 1995

"Since our dreams add up mostly as a series of zeros, then the images of the sum are nothing like the sum of images".

(from Ici et ailleurs)

"You don't save yourself by saving the world. It is a mistake."

(from Passion)

"Metteur en scene is too long. Author seems more valid to me."

(JLG)

In Piero Spila's volume on Jean-Marie Straub and Danièlle Huillet, the author poses the following question.

[...] Do you think that some filmmakers have succeeded in establishing between themselves and the audience the dialogue that the novelist lacks? If so, what reasons do you give for this phenomenon?

Answer by Jean-Marie Straub: "Yes, Godard without a doubt. Because the privilege of the cinematographer is to be able, as he says, to commute between life and art, dream and reality, reality and fiction, poetry and prose, and because that one there, Godard, commutes it best and most often. Also Hitchcock (although it doesn't go down to the level of dialogue by any means), and Bresson no doubt... And one could undoubtedly mention some young filmmakers besides Godard, if all films were born, like all novels, free and equal in right - instead of being consigned (alas! even in Eastern European countries) to a capitalist system of oppression, often supported by the press." *

This quality, which Straub so precisely defines, seems to me to be found in the ending of Prenom Carmen, a film that won the Golden Lion awarded in Venice by a jury led by Bernardo Bertolucci. A way of mending a tear, a personal one, reuniting two stories. Perhaps. Here is the ending of Prenom Carmen.

Carmen who collapses in the arms of the waiter. She is about to die. She asks how they say when all the guilty agonize on one side and the innocent on the other. The waiter says he does not know. In a final gasp, Carmen rails at him. She tells him to do his job: look for imbeciles, it is necessary, as they say.

The waiter says: I am looking, miss, I am looking. And with his eyes he searches around him. You can hear him saying: as they say, as they say. You can hear the last movements of Beethoven's Rondo alla polacca mixed with Joseph's voice shouting: Carmen, Carmen.

Carmen's head gets heavier in the arms of the young waiter with the beautiful voice who watches the last gleams of the day through the glass window. He says: I think they say aurora, miss. **

Jean-Luc Godard was everything cinema could have been. Obviously misunderstood and unloved, especially when his cinema became even freer and bolder with the Dziga Vertov period and video work. He was being arbitrarily, obtusely opposed to his fraternal friend Truffaut, as if to indicate that Godard had betrayed cinema without realizing that his work was (is) anchored deeply in a kind of knowledge and practice of cinema that had made exception its freedom. In the wonderful Je vous salue Sarajevo, Godard declares it this way.

"En un sens, voyez-vous, la peur est quand même la fille de Dieu. Rachetée la nuit du vendredi saint, elle n'est pas belle à voir non, tantôt raillée, tantôt maudite, renoncée par tous. Et cependant ne vous y tromper pas, elle est au chevet de chaque agonie. Elle intercède pour l'homme car il y a la règle et il y a l'exception. Il y a la culture qui est de la règle. Il y a l’exception qui est de l’art. Tous disent la règle : cigarette, ordinateur, t-shirt, télévision, tourisme guerre. Personne en dit l'exception. Cela ne se dit pas, cela s'écrit : Flaubert, Dostoïevski ; cela se compose : Gershwin, Mozart ; cela se peint : Cezanne Vermeer ; cela s'enregistre : Antonioni, Vigo ou cela se vit et c'est alors l'art de vivre : Sbrenica, Mostar, Sarajevo. Il est de la règle de vouloir la mort de l'exception. Il sera donc de la règle de l'Europe de la culture d'organiser la mort de l'art de vivre qui fleurit encore à nos pieds. Quand il faudra fermer le livre, ce sera sans regretter rien : j'ai vu tant de gens si mal vivre, et tant de gens, mourir si bien. " ***

Just like Rossellini, Godard made cinema possible. He liberated it. He always showed and told how it could be continued. It will probably take decades to put the extraordinary Godardian pedagogy of seeing into perspective. Then again, who else would have dared to claim one must learn to see not to read? And it is no accident that his last major film is an Instagram live broadcast, organized by Lionel Baier in which he literally turned the very idea of "social media" upside down. The whole world is quarantined, and Godard opens the doors of his home. Those same ones he had refused to open to Marcel Ophüls et to Agnes Varda by having her find the poignant note: "A la Ville de Douernenay du Côté de la Côte" (which refers back to other histories of cinema...)

"We are ready. Are you ready?"

"I am always ready," the inevitable reply.

Who else could have made an Instagram Live enter the history of cinema?

True to Meister Eckhart's teaching (Only he who erases can write) Godard worked like Lacan "who created images with his words." While the whole world was quarantined, Godard erased decades of exile by allowing a "crew" to enter his house in Rolle.

What resurfaces in my memory today is his desire to always have a conversation, to create possibilities for dialogue. Godard would ask questions. He would floor with his questions, but he was the first, always, to counter the cult of cinema and his own.

"Before one expresses anything, one has impressions. One has been worked on. Something must have gone in if something else is to come out. One works on oneself as a product of processing to become a worker of expression. And in order to do that one must recognize what has entered. Otherwise, neither books nor films are born. Not even a smile."

In thinking about Godard's work, therefore, it would be useful to recall what Frieda Grafe wrote: "Godard's sound/image montages are a unique contradiction to any possible synthesis. They manifest themselves as unreconciled and, by leaving the accidental in a sovereign position, they turn the dialectic upside down."

And, who else, could have said, with such poetic effectiveness, that "with Rome, Open City, Italy regained the right as a nation to look itself in the face" and, at the same time, wonder how the miracle of neo-realism was possible considering that Italian filmmakers separated sound from images?

Then again, the worker played by Isabelle Huppert in Passion says, "After all, work is like pleasure," and reflects on why it is forbidden to film factories. "It's all to do with the same gestures as love. Not necessarily the same speed, but the same gestures." A Godardian self-portrait, almost.

And, finally, in response to those who have blamed JLG for always making difficult films, one could always respond with words found in Passion. "Perhaps it is not useful to comprehend. Taking would be enough."

Giona A. Nazzaro

* Piero Spila (edited by), Il cinema di Jean-Marie Straub e Danièle Huillet, Bulzoni Editore, Roma, 2001, pg. 281

** Prénom Carmen, Pressbook, 1982

*** Frieda Grafe, Wessen Geschichte – Jean-Luc Godard zwischen den Medien, in Astrid Ofner (a cura di), Jean-Luc Godard, Retrospektive der Viennale 1998, p. 78