By Leonardo Goi

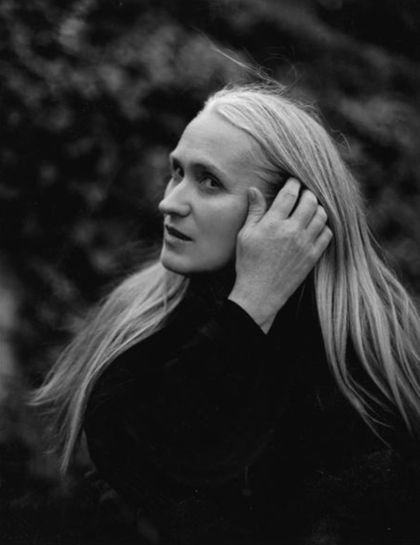

Jane Campion ©Patrick Swirc

Jane Campion ©Patrick Swirc

Leonardo Goi: How well do you remember your first festival? You won the Palme d’Or for Best Short with Peel (1986). What was the whole experience like?

Jane Campion: It was really traumatic, actually. They’d put together a collection of my shorts and a feature I did for the ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation] in a program for Un Certain Regard. But there were all sorts of technical mess-ups. Cannes is really famous for its amazing projections, but because they had to project three pieces they just didn't have time to test them all. The subtitles had kind of bled into one of the films, which made them almost unreadable. It was… well, it was pretty bad! [laughs] Lots of people left because they struggled to figure out what and where the subtitles were. Or maybe they just didn't really like what they were watching. I felt absolutely sick anytime I saw or heard someone leave… I remember going up to Pierre Rissient, this legendary talent scout for the festival who’d put together my program, at the end. “That was really bad,” I told him, “I’m so sorry.” But he thought the opposite; he’d said it had gone well. “How could you possibly say that?” I said. “Because the right people stayed.” And sure enough, I got some great write-ups about the shorts; people really appreciated them. I didn’t understand what was happening.

I also remember Pierre telling us to not get upset if we didn’t win anything. And the night of the awards ceremony he took us up for an amazing dinner on the hills above Cannes. We just missed the whole show! I didn’t ask anyone; I just assumed we didn’t win. And we were walking back to the hotel after dinner, walking along the Croisette, when someone from the Edinburgh Film Festival walked up to me and said, “Hey, congratulations: you won!” I was like, “Won? What? Why?” “Well, you won Best Short; your name was called out and someone from Australia jumped up and got it for you.” So there I was; I’d gone through some pretty confronting moments and some pretty amazing ones – and to find out that I’d actually won a prize… That’s the thing with awards. Even though they may not be meaningful in any way, they’re still something you can wave at everybody and go, “Look, here it is!” They’re tangible. They’re real. And that award was something I could wave at myself too, and feel like I was on the right path, and should start planning a proper feature.

People can be very poetic in what they yearn for, what they're disappointed by, what they love.

LG: You didn’t go to film school right away; first, you studied anthropology. I wonder if that subject shaped the way you approached filmmaking later?

JC: Anthropology was a revelation for me. We had a great professor at Victoria University, in Wellington, where I studied. He’d worked with Claude Lévi-Strauss and was very big in the field of myths. And that’s what really fascinated me: how every culture has its myths, and how those myths, in a subtextual way, perhaps, can describe some of the underlying oppositions and frictions around us. Myths have always served to both hold information and account for the mysteries of a culture. And that’s something I use in my own work, too. It may sound very basic, but whenever I get around to writing something, I go, “Okay, what are the underlying oppositions here?” And then it’s a question of figuring out what to do with those tensions. Do we keep them oppositional, are we going to mediate them, will they be switched or changed? I think anthropology has made me very aware of the surfaces and shapes that operate underneath a culture. And I think that once you start studying it you become aware that all human beings are equal in their intelligence. They all have a language and a mythology, which is equally complex, no matter where they’re from. And I think that gives you a real sense of respect for the differences between you and the others; you know that everyone’s going to have their own way of seeing and figuring everything out. Everyone has their own sort of poem within them; people can be very poetic in what they yearn for, what they're disappointed by, what they love. And that’s got nothing to do with one’s level of education. The bottom line is that we’re all humans, and share very similar yearnings, desires, and needs. Long answer!

LG: But it’s an honest one! I always find it refreshing when filmmakers can be so open about the way their previous occupations or studies might have influenced their craft.

JC: Yes, but I don’t really know much about anthropology! [laughs] I mean, sure, I went to university, learned a bit about the subject, grew up, but my overriding education has always been novels – especially by female writers. When I was young, it was in literature that you’d hear female voices. You weren’t going to hear them in films, because there were very few female filmmakers or script writers.

I’d fallen in love with cinema while in London, where I didn’t know anybody much and would often feel quite lonely.

LG: You pivoted to fine arts after anthropology. Would you also say that painting shaped your approach to film?

JC: I think going to art school, the great wake-up call for me was realizing that seeing is a visual language in itself, and that I had a very old-fashioned, locked-in idea about what art was. I thought I’d just do the same stuff my favorite artists were doing; I didn’t understand that I had to find my own voice. Painting taught me to be super aware of the atmosphere. I remember I was studying overseas and really missing, in a bodily way, what I remembered about the New Zealand landscape and bush, and how deep a love I had for it. That’s why The Piano (1993) was so special for me, and why I really wanted to do something inside that bush; I find that it really talks to me in certain ways. As for the actual painting, well, I got better at it, but I wasn't that good. By the time I got to my third year I started making shorts because I'd fallen in love with films. I just taught myself how to do it with the equipment at the art school. It wasn't much, but I was completely committed. I mean, every waking hour of my life, I’d be doing something towards what I loved. It wasn't painful or difficult; it was just play. I’d fallen in love with cinema while in London, where I didn’t know anybody much and would often feel quite lonely. I just went to see films all the time – that was my companionship.

The Piano

The Piano

LG: One of your avowed influences, David Lynch, has described his creative process as a kind of fishing: there are ideas swimming deep inside you, and you need to muster the calm and discipline to find them and reel them in. How does your creative process work?

JC: It’s a very beautiful metaphor. I always think about my own process as walking into a forest and being patient and quiet enough so that animals can come out and reveal themselves. Your ideas need to trust that you’re going to be there long enough before they can fully share themselves with you. Nobody thinks of an idea; it always arrives from somewhere. And it's usually when you're at your most relaxed, when you're not thinking. It’s magical, in a way. There’s an exercise I invented for myself and now share with my students: spend four hours at your desk with nothing but paper and pen – and some tea, if you like, or a little snack – but no computer and no distractions whatsoever. Just write, and don’t give up until the very end, because it’s usually in that last half hour that the goods arrive. And once you establish that relationship, you do that for however long it takes to finish your project.

LG: There’s also something to be said about the importance of teaching yourself to be familiar and comfortable with the unknown.

JC: Yes. And that was something I really had to learn because I was a little impatient about mystery when I was younger. I didn't understand poetry; I thought it should be like a mathematical equation, that poems could be worked out. And it took me a long time to not feel so threatened [by them] and to realize that poems just have a different way of working. I had to learn to just let them be, that even if you don't get everything about one you can always come back to it later and something else may reveal itself. Keats famously talked about negative capability, the idea that you have to build within yourself a capacity to live in the mystery without reaching out to facts and reason. And that the quality of your work is going to be in some way equal to the amount of time that you can handle that mystery.

As you get older you realize that you need to start taking risks, and that the worst thing is to never even try.

LG: When and how do you think that transition happened?

JC: I suppose it’s a result of just growing up. You become a little more subtle, less black and white. Teenagers are famous for being pretty dogmatic; I think for me it was a bit of a civilizing time! [laughs] And then at some point I made the decision to go all in. To have absolute skin in the game. I decided I’d put everything I had into this effort to make films. There was a time when I was too scared to do that because I was afraid that my expectations regarding my own potential would not be equal to what that potential really was. I withheld it. I didn’t want to explore and find out there was nothing there. But as you get older you realize that potential isn’t of much use for people over 30, that you need to start taking risks, and that the worst thing is to never even try. And that was really a massive, massive decision. It made me feel very bold and willing to fail. And I failed big time, many times. But somehow I was always resilient. It wasn’t like it didn’t hurt – it really did! [laughs]. But I think filmmaking is all about making mistakes, trying stuff, learning. What’s essential is that your enthusiasm must be greater than your fear. Because fear destroys everything. And when you’re enthusiastic, you just can’t imagine failing – you’re just too excited about trying out new things.

LG: This idea of resilience and self-actualization is a good way of thinking about An Angel at My Table (1990). I must confess that when I read you’d picked this as one of the two films you’ll be showing in Locarno, I was a little surprised. It features all the leitmotifs and preoccupations that would surface in your later works, but it’s perhaps not as canonical as other films of yours.

JC: Well, the film plays very well to wildly different types of people. It’s based on Janet [Frame’s] autobiographies, which are remarkable pieces of writing – about a life, about childhood, about an artistic child who didn’t look artistic at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. As a kid, she was this slightly chubby, fuzzy redhead girl. But she had a beautiful, delicate mind. And I think people feel that vulnerability and connect with it very deeply. The most surprising people all have that fuzzy-headed, redhead person inside them, so insecure and unsure. I certainly do.

An Angel at My Table ©Hibiscus Films. Image courtesy of Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga New Zealand Film Commission

An Angel at My Table ©Hibiscus Films. Image courtesy of Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga New Zealand Film Commission

LG: One of the most galvanizing things about the film is the way art is presented as a means of self-reconciliation – a way to make peace with yourself and the world around you. It’s a liberating force.

JC: Well, I got to meet Janet: I had to convince her to give me the rights to her book. I was about 27 at the time; I hadn't even made a short film. But I just loved the book, the first of her autobiographies, and that was the only one that was out and about at the time. And when I first saw her, I remember thinking: this is a free person. She was so truly free. She’d set up this very conventional little suburban house in a little town in New Zealand in the most original way. She had double bricked the front, because she's allergic to sound, and the grass on the lawn was all long, and inside she had separated the rooms with sheets strewn across them, like in a hospital ward – she’d work on a project in one corner, and on another thing in another. It was like her own playpen. She didn’t have a lounge or a dining room, but she did have a bed, and we sat on either side of it, as if we were visiting a sick person… So beautiful. And she herself is a big cinephile. I remember her telling me she loved Last Year in Marienbad (L'Année dernière à Marienbad, 1961) – which I hadn’t even seen at the time. And she told me she really loved bold young people, and that she was going to save [the book] for me, but that I should wait till the others were published in case I didn’t like them. And we’d take it from there. It’s still amazing to think about that.

I guess I find it much more comfortable to explore someone else's work because when I choose to do that it means I’ve fallen in love with it, and I have this passion to protect it, too.

LG: This is also the very first of your literary adaptations, and I’m always fascinated by how, even as you embrace someone else’s story, these films are always unfailingly yours. How do you retain your own voice when looking at the world through someone else's eyes?

JC: That's a good question. I guess I find it much more comfortable to explore someone else's work because when I choose to do that it means I’ve fallen in love with it, and I have this passion to protect it, too. I feel like I understand what it is they’re saying, and how, and I know what to do with it. Adapting Thomas Savage’s book for The Power of the Dog (2021) was an interesting project because there was a much bigger gap between the two of us. He was an older gay man from America; I was a woman from New Zealand. I mean, my parents did have a farm and I had a horse and could ride pretty well… but there was still a big gap between us. I just loved the story. But in that case it was super important to go and do a lot of research in Montana on the ranch where he lived, and where the book was set, and to meet his biographer and his relatives and Annie Proulx, who wrote the book’s afterword. By the end of that research trip I felt like I’d earned my props; I’d paid the respect and done the work, and that’s what it’s about, ultimately. It’s not really a matter of luck. You have to go the extra mile.

LG: The Power of the Dog is a Western, but it’s also that rare film that constantly challenges the tropes and clichés of the genre. I must confess that anytime I think of genre films I think of rules, of boxes that need to be ticked…

JC: Maybe I should think a bit more like that… [laughs]

LG: Really? Because whenever I think of your approach, I feel the opposite. All your genre films radiate a kind of subversiveness. They don’t play by the rules; they break them.

JC: Well, with Thomas Savage’s book, I feel like underneath it is pure, lived experience. This is not genre, in a way. It’s a book written by somebody who actually did live on a ranch, who actually was gay and had an asshole of an uncle who would torture this mother. I think all those things give the novel a specificity that pushes against this idea of following the genre gameplan. I don’t even know if I like genre, to be honest. The only genre film I really like is Alien (1979).

LG: Fair enough!

JC: I love it! [laughs] I dunno if Deliverance (1972) counts as a genre film, but I love that too.

LG: Let’s talk about your approach to directing actors. Do you usually come to set with a very strict idea of all the marks your actors must hit, or do you leave room for improv, too?

JC: I used to be a lot stricter. Now I'm working with actors who like a lot of space and have got a lot to contribute. The hard thing is just being in that dance all the time. I’ve had to develop more muscles for just being in the moment – but I always make sure to prepare well in advance so that I can just surrender to whatever's going to happen on that day. We also do a lot of improvisation around who their character is and how they're going to connect with all the others – which isn’t to say we’d improv scenes in the film. It's just exercises and things designed to give them a very relaxed feeling as to who that person is. There's no effort, no trying, no acting required. And once they sort of feel that character inside them, it's a very special moment.

LG: I’ve been reading a few reviews of your films and it’s striking how often people have resorted to the words “feminine sensibility.” I’m not sure how you feel about that. Does it even make sense to you? I’m asking because even as your works most definitely – thankfully – steer clear of a male P.O.V., they always seem to transcend gender.

JC: As a person, I’m not very gender-y. I don’t worry about myself being a woman or a man or anything like that. Gender’s just not my main identification. If anything, I’m an artist, and that’s got different responsibilities; it’s just much more interesting. I work with other artists, and it doesn’t matter what their gender is. Of course, I’m respectful to everybody; I understand that for some, gender issues are very important, and that if you’re born into a different gender than you identify with that’s very stressful. But I like being around people – around men, say – who aren’t afraid to show their feminine side. I really enjoy that. I suppose it’s hard being a guy because that doesn’t give you much space, sometimes. But when you really are comfortable expressing your feminine side, you know, that's when I think friendship can blossom. When people drop their power issues and there’s plain exploring, that’s what I love. What I feel comfortable with. And my films basically express that. Of course, because I’m a woman, it is a bit different, especially in areas of love and romance. This idea of being a pioneer female director… I mean, I think The Piano was a shock for people. It wasn’t for me, or my collaborators, or my arty people, you know? But for people outside that, to see female desire in a way that insisted on itself, that was very different. And it still looks quite bold.

LG: You used the word pioneer, which is another label I wanted to hear your thoughts on. It’s been thrown at you since your very first projects – and awards – but how do you feel about it?

JC: I never really thought about it, basically. And I truly feel for those artists who work with a lot of expectations on their shoulders, because it feels like you’re almost bound to fail. Of course, I was aware of people like Liliana Cavani, and her The Night Porter (Il portiere di notte, 1974). Talk about exciting movies! You watch it now and it’s still ground-shattering. I recently met Liliana – she’s in her nineties, a beacon of immortality. She’s got this most beautiful clarity. And Lina Wertmüller, of course, who once came to the film school where I studied and suggested we all borrow and steal whatever we needed to get our stuff done. She was so beautiful and dynamic. But basically… I always feel like what came first was the inspiration, you know? I’d have an idea, and I’d work on it. I never thought about anything else. People call me a pioneer, the first person to win this award or that one, but that’s not something I ever focused on or worked towards. If I had, I think I’d have been really put off. Anytime people mention all those achievements, I’m always like, God, that’s a lot. But there’s no freedom in that kind of goal. And where I really do well is… well, I guess in obscurity! [laughs] I like feeling that I’m working in obscurity and then coming out and saying, well, what do you think?