By Hugo Emmerzael

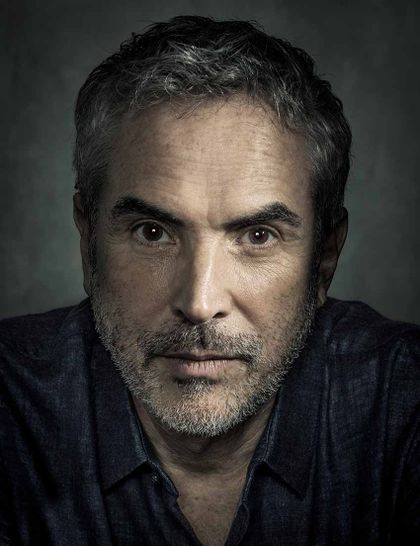

Alfonso Cuarón on the set of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ©Warner Bros

Alfonso Cuarón on the set of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ©Warner Bros

The five-time Academy Award-winning filmmaker Alfonso Cuaron hasn’t made a lot of films, but every single one of them is a testament not just to his skill as a filmmaker but also to his deep passion for cinema.

Be it an intimate drama, a dystopian thriller, or a cosmic journey through space, Cuarón’s visually spectacular films always boil down to one very important question: what does it mean to be human? Receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award at Locarno77, the Mexican auteur opens up about how his films can be seen as an extension of his life.

Hugo Emmerzael: To start on a personal note: it's been a while since Roma (2018) was released. As a film particularly close to your heart, and with plenty of autobiographical elements, I was wondering how it resides in your memory now, seven years after the shoot?

Alfonso Cuarón: Yeah, actually, it feels pretty much in the past already, like I’m looking at it. I can see it from very far away, you know? When I was doing that film, I wasn’t even consciously aware that I was involved in such a personal project. I knew the film took place around my life, but I guess I figured it was not specifically about me. Nevertheless, making it did feel like traveling through time. Revisiting those moments had a kind of therapeutic effect on me, with all the benefits and pain that comes with that. However, it's been a while, and I don’t think so much about my past films. I like to move on into different ventures right after they’re finished.

I think it’s inevitable for any artist that whatever you do becomes a projection of your personal experiences. In some cases, this happens in a profound way, in others, in much more frivolous ways.

HE: These personal flourishes are part of what make your films stand out, even the ones adapted from other stories and books. It reminds me of the opening of your Great Expectations (1998), in which the protagonist says: “I’m not going to tell the story how it happened, I’m going to tell it the way I remembered it.” Would you say that this sensibility is what you specifically bring to your projects?

AC: The person who probably made me aware of this, is my brother Carlos, with whom I wrote a couple of my films. He said that each of my films is like a mirror of a specific period of my life. However, when I set out to do a film, it’s pure instinct. All of it is an instinctive process. So, I’m not stopping to overthink things. I’m just trying to put them together and to realize the film I have slowly built in my head. And still, I think it’s inevitable for any artist that whatever you do becomes a projection of your personal experiences. In some cases, this happens in a profound way, in others, in much more frivolous ways.

HE: Speaking about your films mirroring the times you lived in, can you talk a bit about your first short film Quartet for the End of Time (Cuarteto para el fin del tiempo), which you finished in 1983. It’s a very interesting and strange piece of existential filmmaking. Can you bring us back to those days?

AC: I was at film school and experienced a certain feeling of isolation. I was very young. I might have finished the film in 1983, but I probably shot it in 1981, or even before, when I was about 19 or 20. So, this huge feeling of alienation and isolation was very present in my life at that time. I used to hang out with a friend, who had this tiny apartment in this very beautiful building in Mexico City. Somehow, spending time in that place, the story just came together. Part of it was scripted, but I was also making up a lot as we went along. Around that time, I was intrigued by a film called The Man Who Sleeps (Un homme qui dort, 1974) by Bernard Queysanne with a screenplay by Georges Perec. That film just follows a man in his loneliness, showing his feeling of disconnection. What I remember of my shoot is how I was trying to surrender myself to that space, and working with this non-actor [Angel Torralba], making up scenes as I was going through it. I was very disorganized when I was shooting it, because I really didn't know the right system of how to put a film together and how to organize my shots. During the editing, I couldn’t find my way through the material; one of my teachers intervened to help me, because he said there was, indeed, very good stuff there. He took a couple of scenes, put them together, and showed me how they worked alongside each other. Then I started my editing from there, and that’s the result you see now.

HE: The reason I also ask about this existential film is because I know you studied philosophy before you did film studies.

AC: Actually, I was studying philosophy at the same time. I used to study philosophy in the morning and then film in the afternoon.

HE: I think you can see that background has found its way in your oeuvre, especially the existential sides of many of the characters in your films. I could easily draw a line between the lonesome protagonist of Quartet for the End of Time and Sandra Bullock’s character floating through space in Gravity (2013). Could you say this philosophical background has informed the choices you make in your filmmaking career?

AC: It definitely has. In many ways, philosophy probably played a bigger part in my life than film studies did. It informed me much more and it keeps on informing me throughout my career and my regular life even. You know, I was never an academic, never a real expert in anything. But it keeps informing me and it is something that keeps me current, in sync with the times, and able to explore new ideas.

In many ways, philosophy probably played a bigger part in my life than film studies did. It informed me much more, and it keeps on informing me throughout my career and my regular life even.

HE: It also informs how you approach your characters, who are often so idiosyncratic and inconsistent, and messy in all the ways that life also can be. Even amidst the technological spectacle of Gravity, you put the humanity of it all at the forefront.

AC: As we know, humanity is a messy thing. It’s unreliable and at the same time incredible. It can be filled with a strong spirit of solidarity, it can be very funny, and it can be very tragic. That’s all part of the realm of humanity, and I think that, in one way or the other, all of us have those traits inside of us. This complexity is what makes humanity itself very poignant. This is why I’m a bit concerned about romanticizing people. When you talk about people you admire – let’s say from history or the arts, or maybe just members of your own family – and you romanticize them, you put them on a pedestal. What you then take away from them, stealing from them even, is the most interesting part of them, which is their complexity. And again, I find it all very compelling. I think that each member of this human community is just trying to deal with their own loneliness, trying to make the best out of it. At the end, maybe love is the only solace that we have for that immense loneliness that we’re put on this world with.

HE: So, basically isolation and love would be the two things that connect most of your films in some ways.

AC: Man, you’re a shrink...

HE: That's my work. I’m a film critic.

AC: Very funny.

The language of film itself is based on how the images flow in time. What you can convey in those images, and how those images carry expression, is what I’m always attracted to.

HE: I think that Children of Men is still one of the most important dystopian films of the 21st century, because it gave us very concrete images that captured these feelings of dread and anxiety that a lot of people experience in life, especially when they ponder the worrisome future of the world. Can you talk about the primacy of these images and the way they communicate those deeper feelings?

AC: This is part of the very reason I love cinema. It’s clear that you can make a film without music, without color, without sound, without actors, without story even. However, you cannot make a film without a camera and without editing. Even the earliest films by the Lumière brothers have a single edit, because the shot has a beginning and an end. So, I believe in cinema as a visual medium that is aided by different tools, including sound. But I think the language of film itself is based on how the images flow in time. What you can convey in those images, and how those images carry expression, is what I’m always attracted to. This is why I stay away from too much exposition and didactics. I don’t want to explain; I want you to experience.

Alfonso Cuarón on the set of Roma ©Netflix

Alfonso Cuarón on the set of Roma ©Netflix

HE: You have a very close working relationship with renowned cinematographer Emmanual Lubezki. If we take Children of Men as an example, what kind of discussions did you have with him about how these images carry these kinds of expressions you just mentioned? Do you find an overarching philosophy in your cinematography, or do most of these visual choices stem from the intuitive approach between the two of you?

AC: Well, the seed of everything is very intuitive. We have worked for so long together that we have developed similar approaches. Our views on life and our particular tastes are, generally speaking, also very in sync. When we worked together on Y tu mamá también (2001), I wanted us to start from scratch and do the film we would have done before we went to film school. It was as if we wanted to unlearn how to make films, putting together our own new rules. I decided that we should go with these very wide-angle lenses, so that that information in the foreground would be just as relevant and important as the information in the background. Sometimes the background carries even more importance than the foreground in that film. Then, when we started with Children of Men, we decided that we wanted to take a similar approach. We had decided to follow each shot to its ultimate conclusion, getting the most out of each of them that we possibly could. Even the more classic coverage shots [in that film] have this quality, in the way that they relate to the shots around them in the editing. We also said while we were prepping the whole thing that every shot and every frame in it should be a comment on the human condition. We were not trying to do a science fiction film, we were trying to actually reference the present. When we started conceptualizing the film – it was around 1999 and the transition to 2000 – I wanted to understand the key issues that would shape the century to come, especially since I was very concerned about stuff I was reading and observing.

With my current rate of making films, I honestly don’t have that many more in me. So, I decided, if I’m going to do something, it should be something that wouldn’t be able to exist without me.

HE: I read in an interview you did for The Guardian that Roma was one of the first films you made where you felt you were working without any external influences. It can be quite hard to protect this core part of your own artistry and sensibility, especially in mainstream filmmaking, so what does it mean for you to try to be this authentic filmmaker, as close as possible to yourself?

AC: I don’t think about my authenticity as a filmmaker that much, maybe because I’m not that prolific with my work. My films take a long time to make, because of the time that I put into the shooting, and the time I take for the post-production and editing. Many times, I might have an idea for a film that I get excited about, or I’m offered some screenplays that sound like a lot of fun, but then I think about it like this: somebody is probably also going to do a good, maybe even better, job with this project. Then I tend to think about how long it would take for me to finish this new film. With my current rate of making films, I honestly don’t have that many more in me. So, I decided, if I’m going to do something, it should be something that wouldn’t be able to exist without me. That's pretty much been my rule of thumb for a while now. So, I look for the things that aren’t going to exist without me.

HE: Besides receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award at Locarno this year, you will also present a restoration of Alain Tanner’s Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (Jonas qui aura 25 ans en l'an 2000). What does that film mean to you?

AC: Alain Tanner is one of those amazing filmmakers, who has almost been disappearing from the cinephile consciousness. I hope that with the new restoration of that film, people will become more aware of what beautiful films he made.

HE: I see very strong connections between this film and your work, especially in those idiosyncrasies of the characters that we discussed earlier.

AC: The complexity of the characters in his films is immense. It’s all about the contradictions of people, about the way they say one thing and act in another manner. This contradiction between the selfishness of each character versus their attempts to create an ideal society is beautiful. I love how there’s an almost enlightened pessimism to it all. We were also talking about my cinematography earlier, and it’s very interesting to see what Tanner does with every single shot. This particular film looks deceptively simple, but you can see that each shot is in fact highly elaborate. There’s a lot of humor in the film too, but at the same time a lot of disappointment. I just find it an amazing commentary on humanity, and also our society in general.