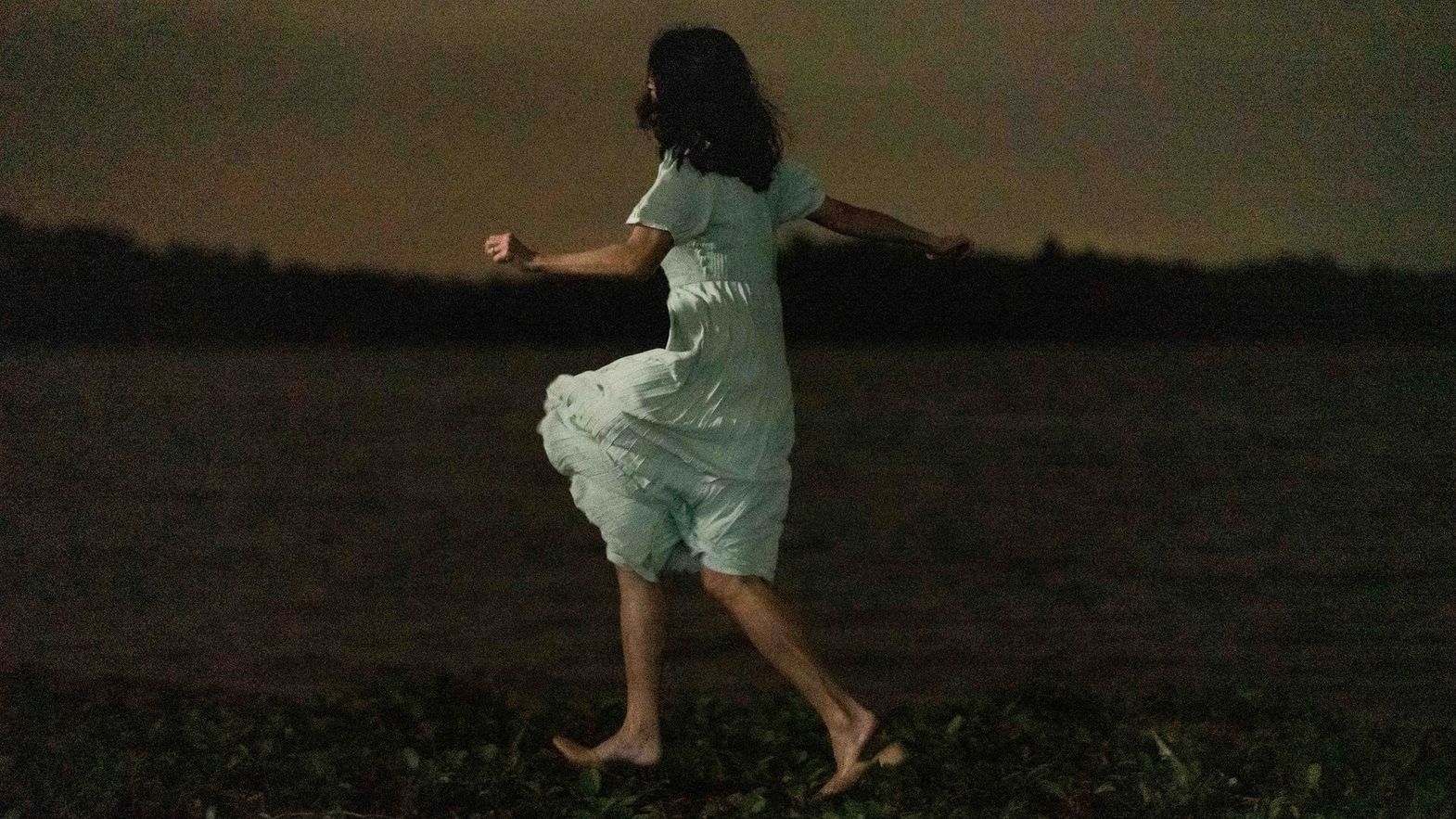

© Momo Film Co

© Momo Film Co

One woman, two men. It’s a configuration whose dynamics – yearnings, jealousies, resentments, betrayals, regrets, reconciliations – have fascinated directors throughout the history of film: from Casablanca (1942) to Jules et Jim (1962) and Y tu mamá también(2001), to name but three, vastly different examples. In Hao jiu bu jian (Dreaming & Dying), Nelson Yeo’s inventive and thrilling debut feature, this eminently cinematic triangle is stripped down then pulled, twisted and bent into wholly new and unexpected shapes.

It starts off simply enough: a class reunion at a hotel by the seaside. Only three people show up. The former schoolmates are now middle-aged and two of them are married to each other. The husband is a boor, and the wife is shy and soft-spoken. They haven’t seen the other man in a very long time. Clearly, there exists an attraction between him and the woman that hasn’t disappeared in all the years of separation. Now that they meet again, it is instantly rekindled, though neither is confident enough to do something about it. Instead, the reunion gives way to a game of repressed longings and simmering rivalries.

Then, things start to get weird. The would-be lovers find themselves in a different story that appears to take place at the same seaside location. Their mutual longing is still unconsummated, but he turns out to be… a merman. Is this a parallel reality or are they merely characters in the book that the wife is seen reading in the main story? (To illustrate the idiosyncratic and delightful sense of humour that runs throughout the film: in one of the many facetious uses of zoom, we first see her intently reading in close-up until the camera slowly zooms out to reveal that she’s sitting on the toilet.) We hardly have time to gain our footing before the narrative shifts again. Now the husband and wife are in the middle of a jungle, carrying a live fish inside a box filled with water. They’re there to practice fangsheng, a Buddhist ritual that involves releasing a captive animal into nature as a means of improving one’s karma.

The film is peppered with such elements from religion, myths and folklore. Yeo fluidly rotates between the three stories, creating a whirlwind narrative that is as confounding as it is exhilarating. Echoes and repetitions abound: the same sentence is spoken by different characters; images recur several times with slight alterations. Are these memories, projections or dreams? Does the difference even matter? Yeo’s minimalist tour de force is an existentialist meditation as playful as it is profound, as well as one of the most electrifying debuts of recent years.

Giovanni Marchini Camia