The Old Oak starts with some pictures of members of the public yelling at someone. A few seconds later we find out they were taken by Yara, a Syrian refugee. Is this beginning some kind of statement?

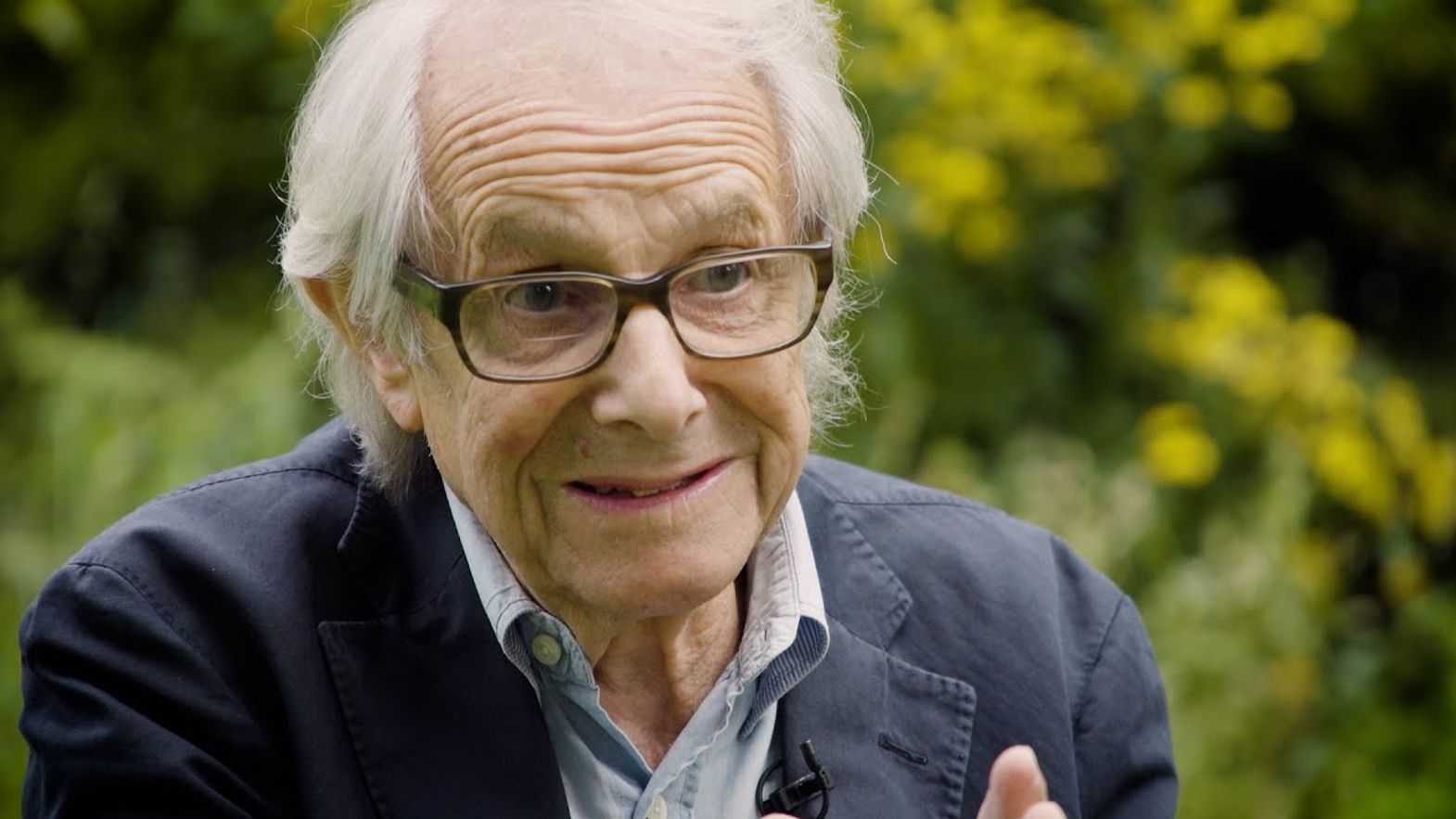

Ken Loach - The girl is a photographer, and it's a dramatic way into the story because it begins with the photograph she's taking of there. They are refugees from the Syrian war. They come to a village in the north of England. And the first thing she sees is angry faces threatening. Complaining. So, we get a sense of the anti-immigrant culture that is pervading our countries now across Europe. And that's the opening tension of the story. Two communities, both suffering and hostile to each other. So that is the turning point of the story. You’re into a story.

Paul Laverty – It’s a big challenge to tell a story about the two communities. There's this complexity in each one of them. Yara is a photographer, by nature and by her work, she's curious. She wants to look out, try to understand. She wants to figure out what's going on around her in a new world. Story wise, it just opens things up for us and it gave her a very interesting back story as well. At the same time, it helped us in her relationship with her father. In terms of story structure, it just really opened lots of doors and possibilities for us.

I want to keep going with the character of Yara, there is a line of hers that stuck in my mind: “When I look through this camera, I choose to see with hope and strength. Is this the way you see the world when you walk behind the camera?

K.L. - I think it's an important line that Paul wrote there, because like anyone in our business making films, you choose what you photograph, you choose the stories you tell. The key question is why do you tell the story? Why did you take that picture? Why did you choose those characters? Why that situation? It is about finding characters that have a simple story, but they shed light on the tensions in society and on the reality of what is happening in one simple story. If you choose the right story, you see right to the heart of how the world works.

P.L. – There’s something I've learned from Ken 30 years ago: the big question is why this story? It’s the most important question now since there are many people who want to tell great stories and don’t get the chance. We should question who commissions and who has control of finances and what stories get made. But as filmmakers and storytellers, just sitting down together with a piece of paper and asking yourself: “What is the best story to tell?” It's an enormous question and one I hope the students here will consider as they as they move on.

Another line says: “Solidarity is not charity.” I think it's a similar line from this movie to others in the past, for example My Mame is Joe. Do you think there’s a connection?

K.L. - Yeah, I think it's a continuing theme. It all relates to the essential struggle in society, between those who exploit and those who sell their labor. And it's an irreconcilable conflict. You can only resolve it by changing the way society is organized. There's an old saying in English: “The poor are always with us.”

Sure, the poor are with us because somebody's ripping them off. Someone’s taking money from them, from their labor. It suits those with wealth to say the solution is we give you a little bit. The symptoms of a class society inevitably will always produce inequality.

P.L. - It has been a theme running through all our films. Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos talk about how much they give to charity. It would be a lot better if they just paid fair taxes, I think that would overcome, many, many problems. It was remarkable when we made My name is Joe, there was no such thing as food banks then. Now Britain pro capite has got three times more food banks. That’s a political choice but it's presented as if it's an inevitability. That's the way the market works, what they do is provide charity to people instead of making conscious decisions that will help people. The Tories now have a policy in place and welfare, for example, that will only support the two oldest children. So, if you have a third child, you'll get nothing. I mean, that is a conscious decision which puts hundreds of thousands of children in poverty and nobody questions it, not even the Labour Party. The Labour Party have decided to support it under Keir Starmer. These are just key questions about justice and the system. Another charity.

How important is it to keep showing movies like The Old Oak to film festivals like Cannes and Locarno?

P.L. - I think this is Ken's fifth time being here. But for me it's the first time. The idea that we're going to sit down and watch a film with 8000 people is remarkable. I find it very, very touching and wonderful. Our local independent cinema in Edinburgh, which has had one of the oldest continuous festivals in the world, just closed, not recognizing how important it is for viewers to put them together. You know, it is a remarkable thing, especially in a world that's so individualized. People are watching their screens; they watch on their phones. And the idea of thousands of people coming along and sitting down together, it’s very profound and really worth protecting, they're actually putting themselves in the framework that they're going to listen to stories from people outside our experience, put themselves in the position when they say: “I will stand in your shoes” for that moment and then they'll go and talk about it afterwards.” I'm really looking forward to it, and very grateful to the festival.

Last, a tricky question: can you pick two or three titles that you feel like: “OK, we just did a great movie”?

K.L. - You can never do that. It will be a thing with which we try to look back critically. The moment you look back and say how good the last one was you're lost. You try to correct what you did in the last one, to be honest, and just keep chiseling away. What questions have we not asked? What contradictions have we not explored? You must constantly be on the front foot, without looking back.

Adriano Ercolani