©Criterion Collection

©Criterion Collection

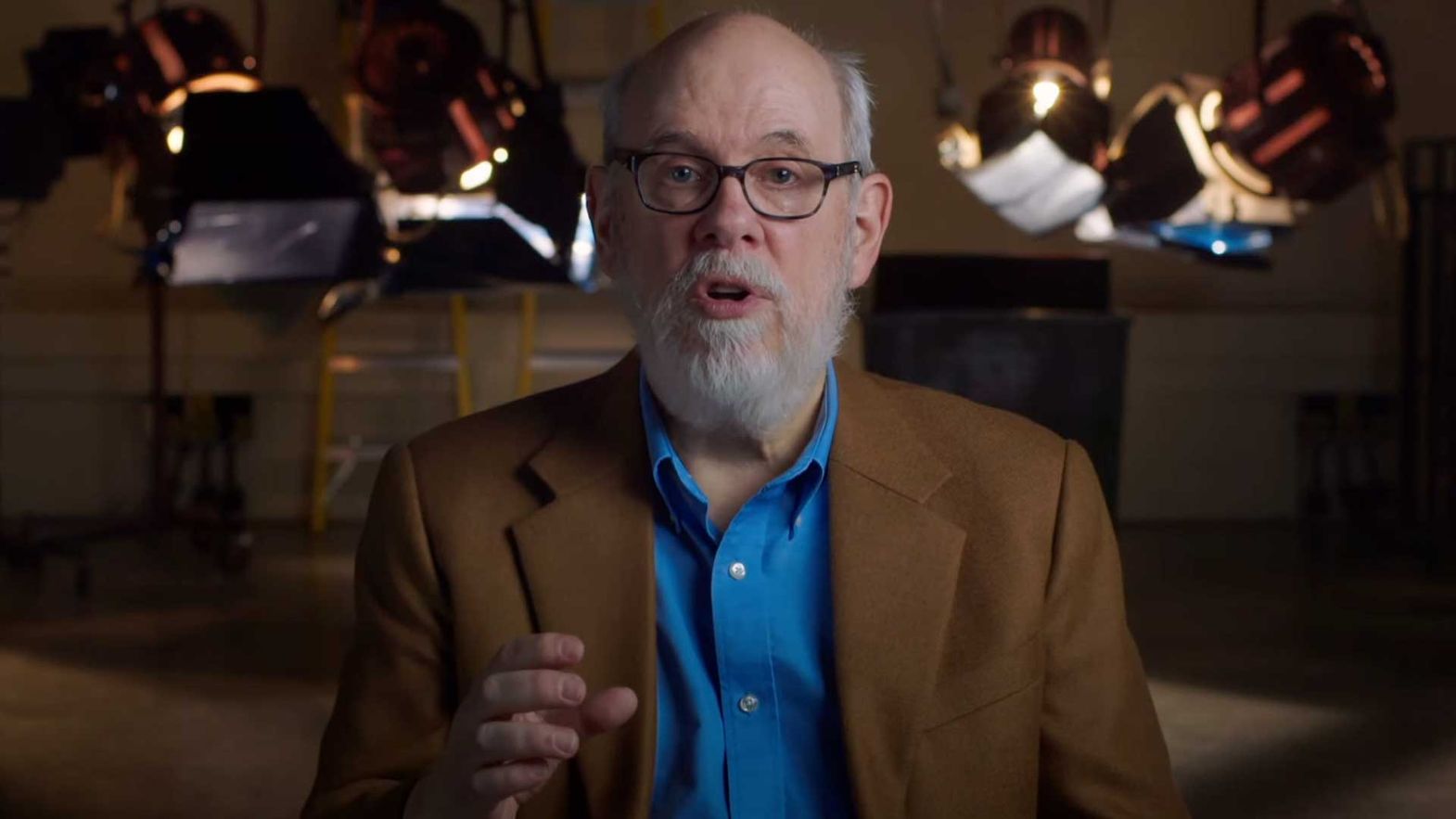

It would not be hyperbole to say that David Bordwell was a dividing line in the history of film scholarship, a clear boundary traced in the sand. Thanks to his erudition and rigor, one can say with authority that there was film studies before Bordwell and film studies after Bordwell. On February 29th, he passed away after a long illness at the age of 76, as detailed in this farewell by his essential collaborator and life partner Kristin Thompson.

The role of a film festival like the Locarno Film Festival is to look forward, to propose several possible futures of cinema while also, simultaneously, reimagining the canon of film history, whether by staging complex retrospectives or supporting significant film restoration projects. But it would be remiss if it didn’t acknowledge the immeasurable contribution of a figure like David Bordwell, whose work charts a course between the varied continents of cinema. His work approached movies, mostly retrospectively, as a science and a practice, as a popular art worth dissecting and analyzing in an accessible way; his crisp prose and meticulous arguments made him beloved by undergraduates and seasoned cinephiles alike.

Now that he has left us, it is possible to take proper account of the invaluable resource his body of written scholarship really is, whether at Observations on Film Art – his personal blog, run with Kristin Thompson since his academic retirement in 2004 – or his books on Hong Kong cinema, film critics of the 1940s, classical cinematic staging, Yasujiro Ozu, Carl Dreyer, or on the art of film in general.

Despite this titanic reputation, David Bordwell was also known for his kindness and generosity. At Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, which Bordwell attended regularly, he could often be spotted in the front row at the various cinemas that showed rarities from the archives. As a very young cinephile, I made his acquaintance. Having sprinted to the cinema for a film, I asked him – without recognizing who I was talking to – to hold my seat (and my pizza box) while I rushed outside to get some water.

When I returned, we got to talking and I realized who had been holding my spot from legions of people asking if it was free. Still, he didn’t hesitate to flatter me. “Well, you know Hou Hsiao-Hsien's early comedies were... oh, what am I saying? You certainly know more about those films than I do. I don’t need to say anymore.” To a very young cinephile, that simple gesture meant an awful lot.

Christopher Small

Editorial Manager and Head of the Critics Academy

I first met David Bordwell at a panel on video essays. He was producing video essays for Criterion while I was still languishing on my YouTube channel, but he claimed that his work was child's play compared to what my generation was doing. This was especially modest given that he laid the scholarly groundwork for using images to study images. His insistence on providing empirical visual evidence went as far as to reproduce stills from film prints for his textbooks. What today is as simple as taking a screenshot was once an incredibly labor-intensive process that he and Kristin Thompson initiated five decades ago.

He was also one of the first to use cinema as a dataset, counting the length of shots to measure their impact on a viewer. I used the same approach to count how much time Hollywood leading actors and actresses appeared on screen. From this I discovered a gender gap in screen time, on which I reported for the New York Times. Of course, David had an insight to contribute for my article: he argued that male protagonists appeared longer in movies because their narratives are based more on the Hero's Journey, while female leads tend to be in social narratives involving networks of multiple characters. It was a whole new field of insight based on hidden data that seemed a world away from the Continental theorization and fixation on poetics that have long dominated film studies. A practice of film studies based on studying film images – who would have thought that such a common-sense approach could be so innovative?

Today's forms of film criticism as practiced in screenshots, video essays and visual analyses are more dependent than ever on close attention to images. In this regard they owe a lot to David Bordwell, in that they operate on the profound principle of seven simple words that describe his philosophy: let me show you what I see.

Like the great filmmakers, David Bordwell created - with observation - new fields of seeing and thus of imagining. Like a poet he fleshed out new possibilities by expanding the horizons of what was possible to see and hear. In him, theory and historiography intertwined in ever surprising forms, as in a generous game full of surprises. But his generosity did not exclude discipline, and the latter never excluded pleasure. David Bordwell was a valuable fellow traveler whose work will be with us for a long time to come.