By Laurine Chiarini

©Gaucho Gaucho Productions LLC

©Gaucho Gaucho Productions LLC

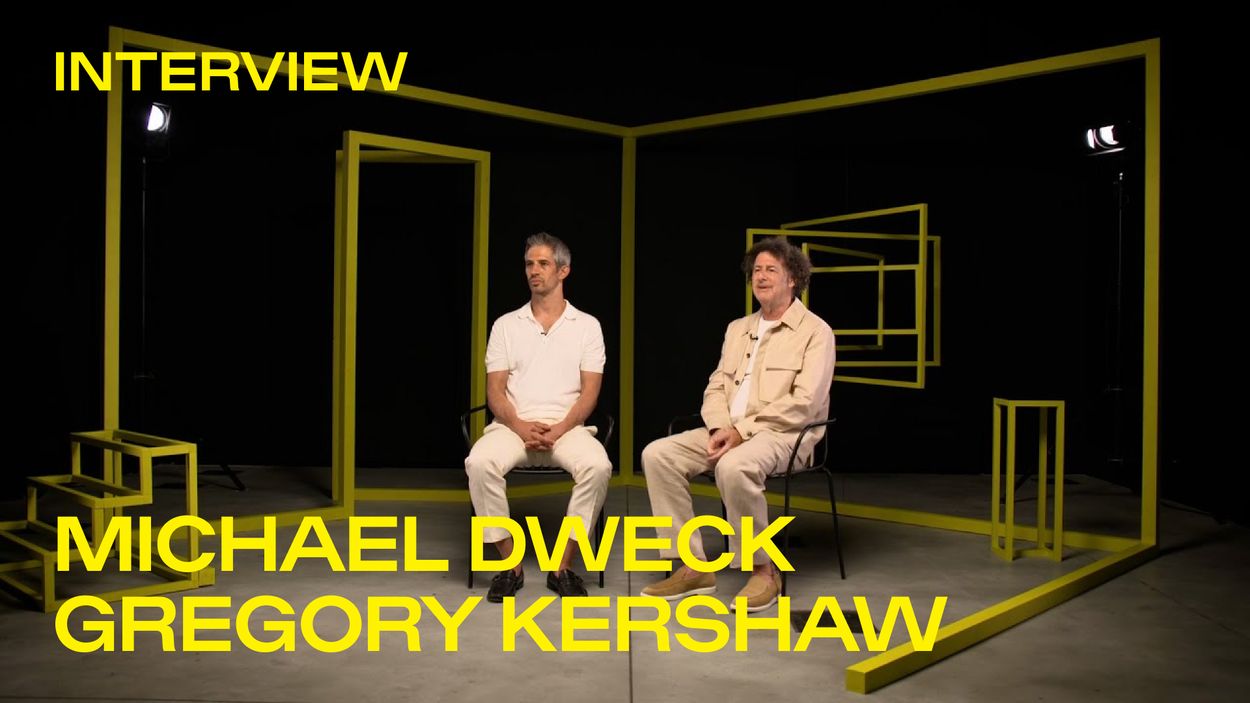

Set in the barren landscapes of the plains of Argentina, photographer and painter Michael Dweck and cinematographer Gregory Kershaw’s visually stunning Gaucho Gaucho (2024), which premieres tonight on the Piazza Grande, is an immersion into the lives of the cowboy community in the Salta region of northwest Argentina, the gauchos. Keeping ancient traditions alive in the face of modernity, these families cultivate and sustain the bond they’ve shared with their environment, the land, and the animals for centuries.

In 2020, The Truffle Hunters, Dweck and Kershaw’s previous directorial collaboration, was intended for Locarno. This was also the year when Covid-related restrictions came into effect around the world, massively reducing the scope of the Festival, and thus the film never made it to the shores of Lago Maggiore. Despite this, the duo’s fascination with the relationship between local communities and their land remained undiminished. Dweck’s wife is Argentine, and he started visiting the country in the early 90’s. In 2021, the two men started doing field research and spent several weeks meeting with different gaucho communities in the northern parts of Argentina, near the borders with Chile and Bolivia. “We were very much drawn to the mythology of the gaucho, which is similar to that of the cowboy in the United States,” the duo told Pardo. “That's when we started looking for the real human stories that are part of that myth. We had to enter these people’s lives.” Indeed, the vintage poster for Gaucho Gaucho suggests much of this mythological fascination: the design is a visual tribute to early Hollywood westerns.

Black and white reveals a myriad of details that a world in colour would miss.

Also known for his photography, Dweck describes himself as a “visual storyteller.” In Gaucho Gaucho, the universe is transcended with an infinity of silver nuances, which the filmmakers call the beautiscope: “It’s our term for a new set of nuances we used to render the luscious beauty we saw.” Coincidentally, analog, or film photography, can also be referred to as argentic photography. Both Argentina and argentic come from argentum, Latin for silver. It goes back to the silver halide crystals that make up the film emulsion in the chemical process used to physically capture an image. Filming in black and white today can prove a risky choice commercially, but it wasn’t even a question for Dwerck and Kershaw. Epic landscapes stretch endlessly across the dry region. The houses are made of mud, and when flour is tossed in the air by the women in the kitchen, you can see almost every speck of it. “The textures were magnificent. Black and white reveals a myriad of details that a world in colour would miss.”

Just like with black and white, sound is used as a formal building block to deepen our immersion in this world. A piece from Bizet’s opera The Pearl Fishers contrasts beautifully with the clean sounds of nature in the following scene. The two men, both music lovers, would listen to Argentinian rock while initially scouting locations. They recall that, naturally, “when [they] got into the editing process, [they] had accumulated a big playlist.” The filmmakers’ eclectic musical tastes and ear for rich soundscapes are a perfect complement to the images, a way to convey feelings beyond mere impressions. It makes Gaucho Gaucho into, as they put it to me,“a dreamscape where the viewer is lifted out of reality in subtle ways, into how the moment feels rather than how it actually is.”

©Gaucho Gaucho Productions LLC

©Gaucho Gaucho Productions LLC

The opening scene provides such an example of wholeness, when the physical form we see is perfectly still and its precise shape, indistinguishable. A few blades of grass move in the wind; then a snorting horse wakes up, shifts in place, and so does its rider, who had been sleeping on top of his mount. “That shot was a bit of a miracle”, Kershaw remembers. “We knew that people slept on their horses, and it was such a fascinating idea. It captures what we are looking for, a moment of magic you can’t really predict.” The pulse of the rider practically matches that of the horse; this is when complete trust is achieved, as man and animal practically become one.

When asked how the shooting days were planned, Kershaw explains that “Part of the beauty of the documentary process is that you are constantly being surprised: you start filming with an idea of what it might be, and it turns into something so much more beautiful.” When wonder is at the end of the road, patience may be a cinematographer’s greatest virtue. Dweck and Kershaw dedicated months to building relationships with the people they filmed, to gain their trust. “We wanted to immerse the audience in the beauty we saw. But first, we set off to observe these people’s lives; not just listen and watch.”

Blending in, the two men would sit with the families at the dinner table, a strategic focal point of all the conversations. They never felt the need to direct their subjects. “We’re a small crew of four. Our protagonists could live their lives, unencumbered by our production process,” said Dweck. In most of the interior scenes, the frames are static, allowing for a minimalistic presence of the technical gear. When groups of riders gallop in the open-ended pampa, they are accompanied by seamless tracking of their movements by the camera, sometimes in slow motion that enables the viewer to study the beauty of man and beast working together in unison. Only once do those movements become hectic: an onboard camera follows the furious bucking of a horse during a jineteada gaucha, a rodeo where riders are required to stay on an untamed horse as long as possible. This moment is, crucially, the only time in Gaucho Gaucho when the domination of man over animal is achieved through violence.

We were filming a world that was not just fragile, but fading.

“We were filming a world that was not just fragile, but fading,” Dweck tells me. In Argentina, the draught that results from global warming is a serious threat looming over the traditional cattle rearing and its methods. “What we saw there was quite different [from what we expected]. Unlike elsewhere, the parents and grandparents want the tradition to live on. They really encourage younger kids to learn the ways it’s done.” In the film, we see the only woman in the male-dominated world of the cattle-rearing gauchos. Encouraged by her father Tati, 17-year-old Guada is determined to become a gaucha. Solano eagerly shows his 5-year-old the tricks of the trade. Old Lelo complains to the local healer that he wants to feel young again. “From observing him, we are now inside of his head,” Dweck comments. “There is no other medium like film to celebrate the beauty and the passion of these extraordinary humans on a grand cinematic scale, and to share our vision of what a fully realized human life can be.”