By Christina Newland

In 1924, a pugnacious businessman who grew up impoverished in a New York tenement co-founded a movie studio. That studio came to be Columbia Pictures, and that man its long-reigning mogul Harry Cohn. With humble beginnings and an economical eye for budget, Columbia had a knack for turning out ingenious motion pictures with talent on loan from other studios, from Cary Grant to Carol Lombard. Those films would become stone-cold exemplars of their genre – The Awful Truth (1937), for instance, or Twentieth Century (1934).

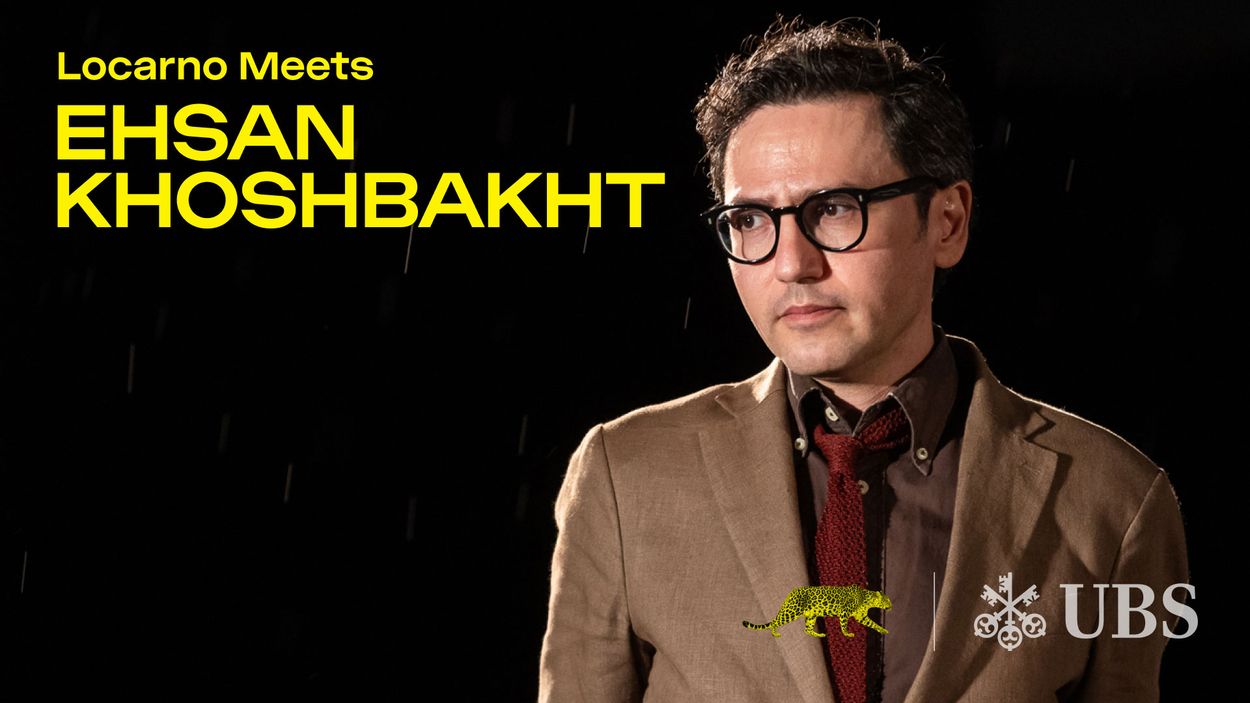

Programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht has dug deep into the Columbia vault to curate ‘The Lady with the Torch: The Centenary of Columbia Pictures’, a 40-film Retrospective that will show at Locarno77. Looking back at that studio’s golden age and beyond the canonical titles, such as It Happened One Night (1934) and Gilda (1946), Khoshbakht unearthed the work of little-known B-directors and stumbled upon strange genre cycles, such as the delinquent girl flicks of the 1940s.

We caught up with Khoshbakht to talk about his rationale for the program, some of his stealth favourites, and how watching too many Three Stooges shorts almost drove him to madness.

Tell me a bit about your initial idea for the retrospective.

The initial idea was a bit more radical – celebrating Columbia’s centenary through B-unit productions and forgotten films. No Frank Capra, no Howard Hawks screwball comedies. I gradually came to my senses. The current version of the programme is a bit like the studio itself, made up of a quarter canonical classics, a quarter lesser-known films by masters (there’ll be a restored version of Gun Fury [1953] by Raoul Walsh, for instance), a quarter unseen films (Edward Dmytryk’s Under Age [1941]) and a quarter films by and about women, in front and behind the camera (Craig’s Wife, [1936]). So there will be Capra and Hawks. It is silly doing any retrospective on any subject without showing a Hawks picture.

At a certain point, Columbia was well-known for screwball comedy, and then after the war for the B-noir, but of course the studio made all manner of genres. How did you approach wanting to curate films both in and outside of the genre parameters people might expect?

I tried to avoid thinking of the studio output in terms of genre. Instead, I followed the directors’ trajectories. Let’s see where Lew Landers started in 1941 and what he did before calling it a day at Columbia in 1953. In between, you have 54 films and you have to find the meaning behind that man’s efforts. I must confess I was wary of getting too much into the Columbia noir which is perhaps now the most famous and the most widely circulated of the studio’s postwar films. The reason was I wanted to focus on the underseen and the less obvious.

The Mysterious Intruder, ©Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved

The Mysterious Intruder, ©Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved

In your research, how many films did you track down and view? And what patterns began to emerge, if any?

I started by printing out Columbia’s release calendar, 1929-1959, and viewing them and marking them as if a secret code to a parallel universe could be discovered. The idea was to watch a) a minimum of one release per month; and b) to identify trends, series, cycles, and go for the most representative titles belonging to that group of films. I think I have seen close to half of Columbia’s features from that period, excluding the foreign film releases, since they also distributed films like Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai, 1954). Another lifetime is needed to fully cover every Three Stooges short, even without mentioning the potential threat to one’s sanity that that entails.

But even now that the programme is fully assembled, I simply can’t stop watching Columbia films; I need to be committed to a rehab centre. The unpretentious and modest artistry of them simply appeals to me. Now when the characters open their mouths, I can roughly tell what the dialogue is going to be. So in a way, there is a parallel universe of Columbia Pictures and now I’m living in it. Regarding patterns in what I discovered, I can say that what actually caught my attention was the period when there was no pattern, as in the late 1950s when confusion reigned at the studio. Watching those films, you wonder “What’s going on?” you can feel the studio was trying to hang onto anything it could before the eventual freefall due to changes in the economy of Hollywood.

The biggest lesson I have learned, which should make auteurists very happy, is that at the end of the day, it is the director’s style – good or bad, original or imitative – that stands out at Columbia.

Often, Columbia’s history is largely viewed through the prism of Harry Cohn and his personality. Were you interested in putting the focus elsewhere with this season?

He was a fascinating figure. His instructions, notes, and involvement – often delivered in very crass language – shaped many of the studio’s projects. There are some independent projects in the studio that became enormously successful, but which Cohn hated since he had no say in them. He loved the control. Yet, Columbia was a freer studio compared to MGM or Twentieth Century-Fox. There was a great degree of flexibility and trust. And I think Cohn trusted the artists more than Zanuck or Selznick did. The biggest lesson I have learned, which should make auteurists very happy, is that at the end of the day, it is the director’s style – good or bad, original or imitative – that stands out at Columbia.

What do you find are the biggest misconceptions about the studio and its history?

Whenever somebody refers to “the genius of the system”. As I said, the directorial voices at Columbia Pictures are those heard most loud and clear, so giving all the credit to the studio doesn’t make sense. The studio provided the fertile ground upon which they worked, as well as the impeccable technicians and the improbable plots and scenarios. The rest was up to people – talented or mediocre – to make something of them. But if one looks closely at Columbia, it becomes clear that it completely differs from other studios because of the blurred line between A and B films in their output, the hybridity of the genres they worked in, and the remarkable reliance on outside talents and independent productions. Experiments were allowed. Leftists and Communists were tolerated. All as long as things were kept under budget. The budget was Cohn’s eleventh Commandment.

How much did the availability of films effect the selections you made?

This has been the highest degree of freedom and ease of access I have so far experienced as a programmer. Sony Pictures Entertainment owns Columbia toda, and the Sony/Columbia archive people are among the most respected in the cinema archive world. Grover Crisp and Rita Belda helped enormously.

It completely differs from other studios because of the blurred line between A and B films in their output, the hybridity of the genres they worked in, and the remarkable reliance on outside talents and independent productions. Experiments were allowed.

Talk to me about how you see women’s roles in the films you’ve chosen. What was unique in some of the depictions you chose to curate?

Compared to other major studios, Columbia was the studio of women. Not only in the stories and characters, but also in people involved in making the films. There were more women in the artistic teams and the crews than in other studios. At some point, Columbia was the only studio that had a female executive producer, Virginia Van Upp, who was also a superb writer. And there were many fine writers like Gertrude Purcell, Mary C. McCall Jr., and Fanya Foss. That aside, Columbia had some kind of girl-movie obsession going on. For almost every type of film made at other studios with men in the leading roles, Columbia would do an all-female version of it. If Warners did Wild Boys of the Road (1933), Columbia responded to it with Girls of the Road (Nick Grinde, 1940), about a gang of tough hobo girls. The gender reversal extended into prison movies and even war films and gangster films.

Is there anything which we haven’t discussed and would like to point people toward as a recommendation?

The book, which will be in English and published by Les éditions de l’œil. It features nearly twenty new essays and many rarely seen stills from the archives of Sony/Columbia and Cinémathèque suisse, both the partners of the Locarno Retrospective. In the book, which will be available during the festival, there’ll be, among other things, first-time studies of some of Columbia’s underrated contract directors such as Roy William Neill, Nick Grinde, Alexander Hall, and Charles Vidor.