By Christopher Small

A stuffed leopard sits atop a wooden beam. In this studio in Oxfordshire, soft lights, diffused by mirrors, swing one way and then the other, struggling to settle on a point of illumination. A long lens swivels left and right as its operator rehearses specific movements.

Everything is set in place. The plushy is removed. A heavy door slides open and out saunters Bagheera, the would-be face of the Locarno Film Festival. His principal trainer walks besides him, clutching a spear. Impaled on its tip is a lump of red meat the size of a fist.

A wall of metal lattice separates the leopard from Tim Flach, the world-renowned British wildlife photographer, and a team of technicians manning the various sound desks and lighting stands arranged in a semi-circle around his camera.

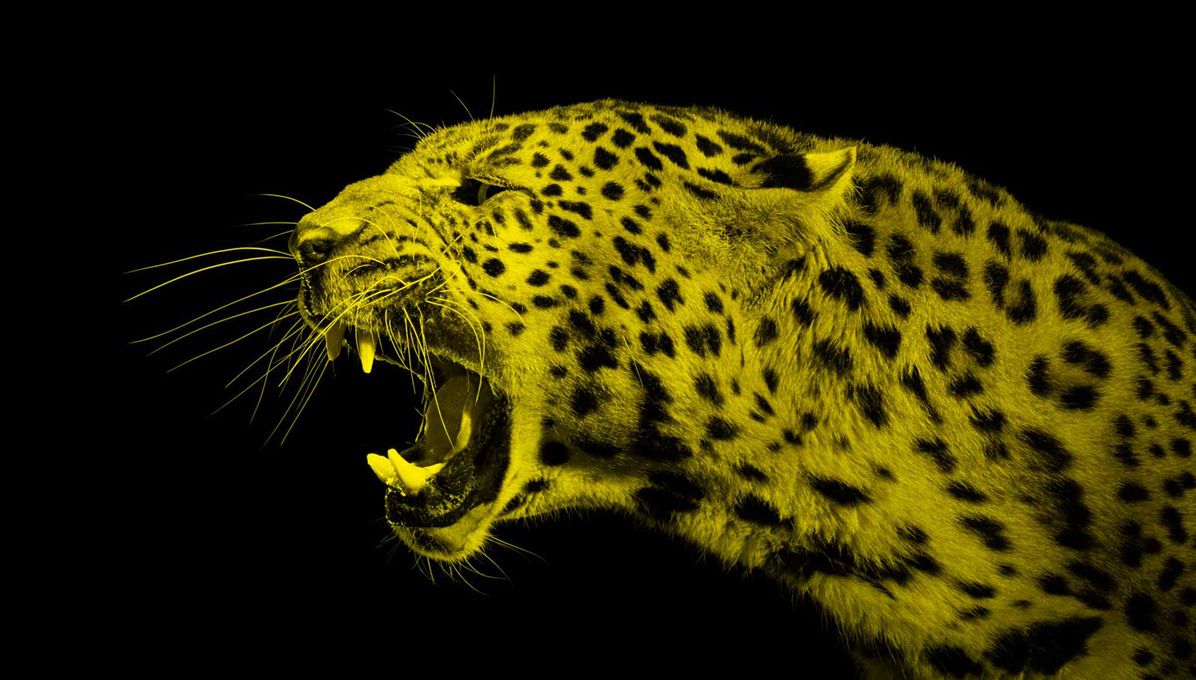

Flach peers into the eyepiece. The leopard hops up onto the wooden beam and takes a few heavy steps. The trainer swings the meat towards him and then yanks it away. Bagheera snarls angrily, his sharp teeth bared. Flach’s camera lets off a series of rapid clacks: chk, chk, chk. Got it.

Bagheera gets his lump of meat; Locarno gets its leopard.

“We have a very small window to get the shot,” Flach tells us from his studio in London, several months after the shoot. “Working with a leopard is a little like dealing with a celebrity – you really have to have your act together. Nothing can be left to chance.”

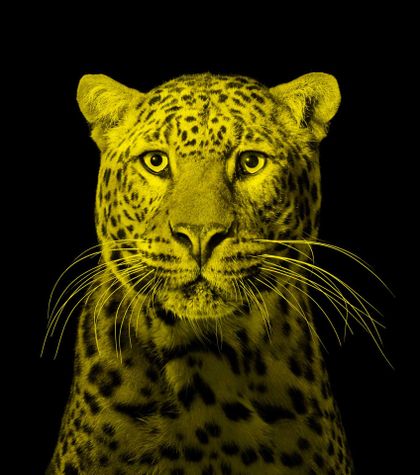

At Heythrop Zoological Gardens, Bagheera roars a few times for the video team and struts back and forth across the beam, a movement captured for the Locarno Film Festival’s pre-film trailer. After that, it was time for the still photos: another fearsome snarl and a more placid front-on shot, his lips drenched in drool as he peers at another chunk of dinner.

Many people who ask about the previous leopard, the Locarno Film Festival’s public face since 2008, are under the impression that it is not real – perhaps computer- or even AI-generated. But that leopard was also one of Flach’s real subjects, photographed in an era when its walk across the screen was captured in 35mm, illuminated by huge, cumbersome batteries of lights. Jannuzzi Smith – the same design studio, working with Tim Flach – was responsible for the production on both shoots.

“Locarno previously had no leopard whatsoever. Designs and spots, yes. But there was no leopard walking before the start of a film, for example”, Michele Jannuzzi told us. “We made a proposal to [Artistic Director] Frédéric Maire in 2006 or 2007; once we had decided against the idea of animation, we had to go to England to find our photographer and find our leopard.”

Both shoots took place 15 years apart at Heythrop Zoological Gardens with the same animal handling team, the same photographer, and much of the same crew. “In situations like this one, you can’t have anything that might make it challenging or dangerous for the person inside the cage with the leopard”, Flach continues in his very English, matter-of-fact way. “We must set up lights that allow the cat a safe passage in and out of the space. If a light were to be knocked over accidentally, it could spook him. And Bagheera is an animal that can do serious damage if he gets scared.”

“Indeed, there's always an uncertainty with animals, especially big cats. We are no different, are we? We’re not in the same mood when we wake up from one day to the other. With that front of mind, we do our work near where they sleep and where they play. They’re not travelling anywhere, there’s no stress. If they began to be confused or feel scared, that’s when it becomes quite dangerous. Our job is to make sure everything is comfortable and familiar.”

Flach brings more expertise and experience to these kinds of shoots than pretty much anybody. Across his various books, exhibitions, and professional commissions over the years, he has – photographically speaking – captured the essence of all manner of big cats, and in many distinct contexts. “As the old saying goes, dogs have owners and cats have staff”, he quips as we marvel at the sheer variety of the felines in the pictures that adorn his studio.

Lions. Tabbies. Panthers. Royal White Tigers. Cheetahs. Housecats. Leopards. These photographs bear out that depth of experience. Though the shoot with Bagheera comes at the behest of the Locarno Film Festival and Jannuzzi Smith, Flach is engaged in a long-term project about felines in general. Together with some of the world’s leading evolutionary biologists and neuroscientists, the seasoned photographer is trying to get at the essence of our relationship with cats big and small, and what makes them such crucial parts of the lives of so many people. “Why are house cats more popular than dogs? Look, it’s like when Tim Berners-Lee, the founder of the internet, was asked what was most surprising about his invention”, says Flach. “His response was, ‘Kittens’ ”.

Bagheera is now the official leopard of the Locarno Film Festival. These new shots, intended to last as enduring icons for the Festival, were captured over two days.

“Technology and its evolution are of course hugely important to what I do”, Flach says when we put this conundrum to him. “As the equipment gets more advanced, it gives us more opportunities to capture the requisite images in rather brief shoots like this one. With the leopard, I’m using sophisticated eye tracking technology to make sure I don’t miss out in a very narrow window of opportunity.”

For all the difficulty of working with a big cat like Bagheera, the results speak for themselves. On the day of the shoot, the leopard gets tired after a couple of hours, a shorter period than was hoped for. “I, like many photographers, live by the old maxim ‘It’s never the last shot’ – even when working with animals,” Flach adds. “But with a cat like that, the maxim is more like, ‘Okay, understood’ ”.

Bagheera, sitting where the stuffed leopard toy once sat, has without realizing it become the public face of the world capital of auteur cinema.

Special thanks to Fabienne Merlet and Michele Jannuzzi.