The first Saturday of the festival is by no means a holiday – the third program is comprised of films with the common theme of impuissance.

Be it futuristic technology that monetizes our minds, the political games at play in wars that know only losers, or the oppression of the working class – this program gives little time to rest and lots to reflect on. But there is one exception as one film also highlights possibly the only moment of complete helplessness we so desperately wish for: when love strikes.

Cyril Schäublin returns to Locarno with Il faut fabriquer ses cadeaux after debuting his first feature Dene wos guet geit in 2017, earning a special mention from the jury.

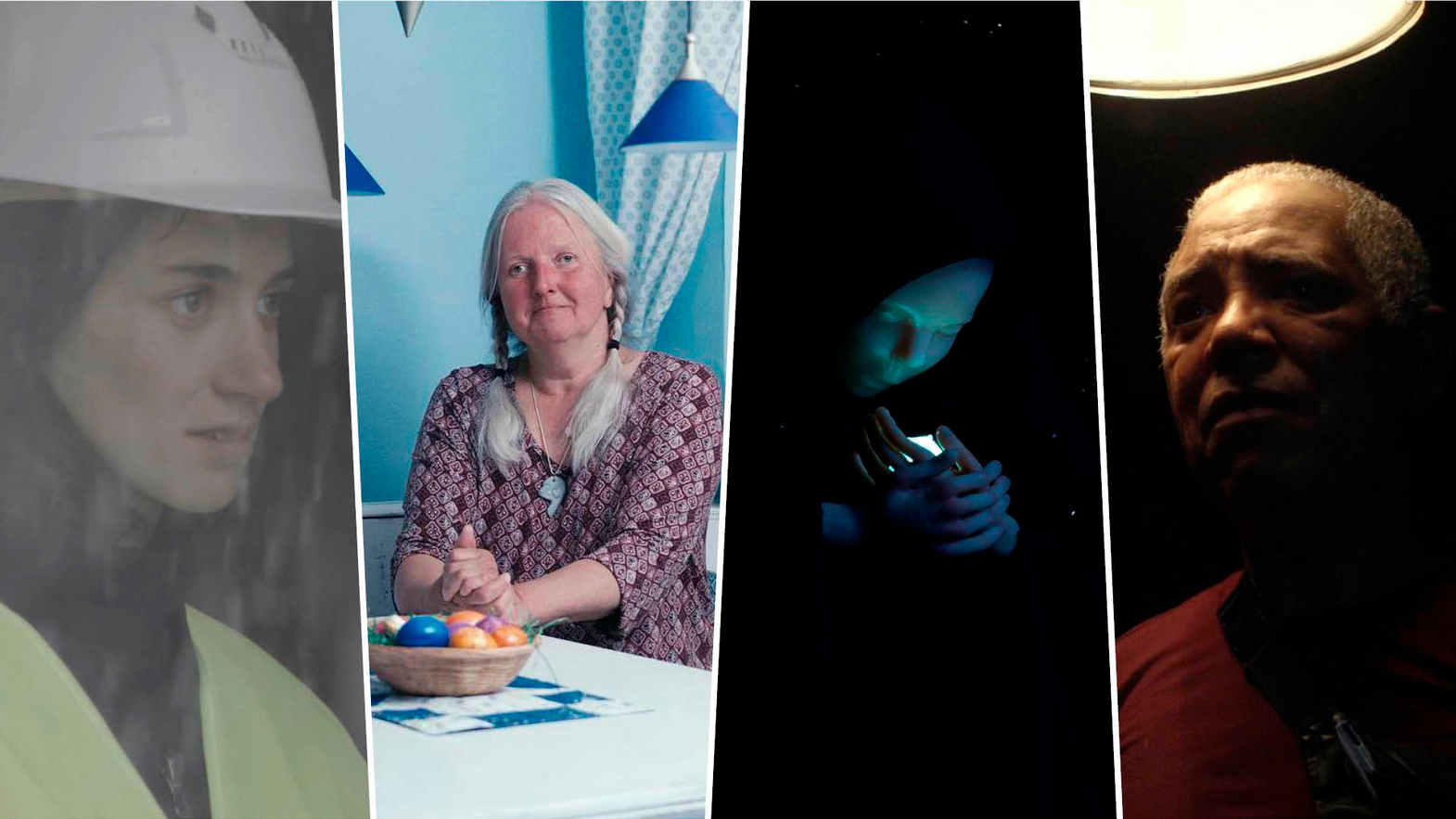

Set in a snowy near-future Switzerland, new technologies are making the rounds. A device that apparently can read minds and a new public hologram that you can kiss in exchange for money.

Three colleagues, who occupy themselves with incomprehensible work, discussing technologies, both praising and acknowledging their abilities, understanding their deceitful manners while not opposing them.

The dependency and powerlessness when it comes to new technologies manipulating and misusing human desires, as is already widely seen in today’s world, is juxtaposed with the dry and superficial discussions that are filmed with a calm and observational camera.

The message is clear: you must earn your happiness.

Co-directed by Pascale Egli and Aurelio Ghirardelli, Ding (Thing) is a documentary on a rather rare topic: the love for objects. The two protagonists, Valentina and Sonnili have spent most of their lives in love with various things.

In interviews, they open up to the camera but not in an effort to justify, due to the social preconceptions, incomprehension, and disapproval, their “condition,” but simply tell the viewer how they came to love objects, what it means to them, and what love is to them – the only conclusion to draw is that their love is like any other between two human beings. They just couldn’t help themselves.

The film approaches this subject with the utmost respect and care, managing to offer an unprejudiced gaze without losing its humor, which is so amply provided by the protagonists, in the process.

Night is a beautiful yet sorrowful stop-motion animation by Ahmad Saleh.

As darkness falls over a war-ravaged village, Night herself nurses the survivors by bringing them sleep and some hours of relief by letting little glimmers of hope fall onto the people. Yet her efforts seem without avail for a mother who is desperately looking for her child.

The visually captivating and mesmerizing set design, paired with the calming voice of Night and the musical accompaniment, stands in stark contrast to the pain and horrors of war the film so poetically touches upon and only visualizes in its periphery.

Yet the brutal reality of war and its media images are ever so present and seems to pierce through the film – and the prone bodies of sleeping children could just as well be their corpses.

Crushing sounds of heavy machinery make up the rhythm of societal destruction in Francis Vogner dos Reis’ directorial debut A Máquina Infernal.

Capitalism, corruption, and private gain are burnt into the ruins of a soon-to-be bankrupt factory that has its employees controlled – the work is badly paid without any guarantee of continuation, but there are no other job opportunities.

While the film starts out with an observational tone, documenting the short-term entry of a new worker as she joins her colleagues on the factory floor, it slowly transgresses into a different paradigm where workers are not only the victims but the factories the oppressors.

With every minute, the film heightens its tension further as the capitalistic society’s demons make their presence known, and the powerlessness of the working class is exemplified.

Valeria Wagner

News · 13 | 08 | 2021

News · 12 | 08 | 2021

News · 11 | 08 | 2021

News · 10 | 08 | 2021