The Magic of the Mundane

By Sadia Khatri

Sadia Khatri is a writer based in Karachi. She has worked as a journalist and now writes fiction, essays, and poetry. She is also co-founder of the feminist collective Girls at Dhabas. Currently, Sadia is working on her first non-fiction book, and writing her first short film.

Things it takes me several days to figure out: maps are useful but only so much, the Fevi is on the other side of town; do not refer to every filmmaker as an auteur; always carry an umbrella; people will not chide you for knowing so little about film, in fact they will respond with kindness and encouragement, often furnishing generous watching lists. I was a writer turned accidental critic attending Locarno Festival last year for the first time, attending any film festival for the first time. I found myself thinking: this is a ten-day film set where all actors are essentially cinephiles playing themselves, and I am an extra, scrambling with my last-minute schedules, marveling at fellow critics’ pre-printed spreadsheets.

“Don’t go by the blurbs,” a fellow critic suggests, helping me plan the day’s films. “They rarely tell you anything. And watch things you would never watch”.

*

notes, aug 2019

space dogs (elsa kresmer, levin peter) - chilling contrast b/w the two stray dogs [on moscow streets] and the dozens experimented on for space travel. esp knowing none of the dogs experimented on made it back to the streets. in the archival footage, camera is clinical, still, like recording some tutorial. contrast with fly on the wall camera following the stray dogs freely roaming moscow, going about their day (they direct) as they linger lounge love - seem to inhabit a whole other city than the ones we know - how little I know cities. gog-city runs on different time, its borders are parked cars - when I come out of the theatre the street feels so low, i want to see it from the dog’s eye level—

143 rue de desert (hassen ferhani) - why mallika came to run this trucker’s shop in the middle of nowhere, we don’t need to know - the stories in the present matter, encounters can be windows to whole lives. not once we move from mallika’s tiny shop - truckers, travellers, passersby - what we get to know is thru her conversations with other people. unscripted, improvised. long shots of mallika sitting in her chair, of the light thru the tiny window - something about a daughter, again specifics unclear, then she’s talking about a missing cat, wait, cat and daughter same, it doesn’t matter who she lost first just that her grief is unloaded and i am crying w her.

bird island (sérgio da costa, maya kosa) - hardly much dialogue except when the healers have to instruct each other. healers fiercely caring, quiet, strange, strange location: film set inside the center/clinic, an island, a sanctuary, a fool’s errand? but they save many animals and it is the life we owe these creatures which seems to be the point of the film— the majestic owl, framed by branches and leaves (he survives), the consistent sound of birds and wind, long shots of hands caressing birds, bandaging them, all attention to what is precarious, what needs tending to and can be tended to— “in the outside world something is changing” - from here the outside world feels too loud, too fast—

*

I couldn’t tell you then why some of these films stayed with me. If I like something immediately I am critical about it; what is automatic is not always thoughtful. These films made me reflect, but also unsettled me. Growing up mainly on Rajshri and Yash Raj productions, that particular brand of fast-paced absurdist melodrama that is archetypical of North Bollywood cinema, it makes sense in a way: all of them oppose, temporally, politically, aesthetically, the canon I reluctantly carry and secretly hate. But there is more at play here than a simple contrast with the films of my childhood, though I am in no rush to know. Struggling to pin down the reason some stories and poems and films move you, is a gift: it means they have the thrilling potential to transform what I know about myself. That they have touched some deeper, primal nerve.

*

Getting to know the other eleven critics, the debriefs and discussions in-between, afterwards, over dinner, long hours at the Kursaal, walking down to the lake: what the world feels like moving from each portal of a theatre to pockets of air and sun and free beer at Mono Bar, is nothing short of a fairytale. Film is a magical medium opening my heart in ways I had not thought possible. You know that constant, subtle charge, when you’re so sure you’re pulsing with some kind of beginning? And people around you are offering ways to make it happen? At twenty eight I was so certain I knew what to do with my life, but looking back that whole year was a kind of baptism. I am failing to write about my time at Locarno without the awe of someone who did not love films before, of course I did, but not in this way, where often I wonder if I might have chosen the wrong medium; should be making films instead of just writing about them. Never had I spent day after day moving from boxed room to boxed room, cinema to cinema to cinema, so by the end of it, you reach a kind of state, depending on the pace of sound and drama you encountered that day, a haze that is solely your own, and then you meet your friends and wonder what universes they have traversed each day, too. I will never forget Domenico, surfacing from Bela Tarr’s seven hour long Santantango, like he’d come from a swim in the deep sea. Glowing and elsewhere. This is another thing it takes me a while to figure out, this not-so-secret spell: you can conquer time, hack it differently, when you spend all day inside cinemas.

*

Sometime this year, has the pandemic begun yet, what are clocks even, all I know is that Locarno feels like a lifetime ago and I can’t watch films. I return home from that magical Swiss town to greet the first setback in my fairytale: my boyfriend breaks up with me. I lose the person I love most in the world, my film-watching buddy, someone pivotal to shaping my love for cinema beyond Bollywood. After that, it is hard to get through movies. I try Mother India, thinking a classic might work, takes me two weeks to finish. I put on Ozu’s Floating Weeds but keep pausing it every few minutes, a terrible thing for a critic to admit. Kieslowski’s Three Colours Trilogy is incredible but too close to my grief. As the loss of one love makes you doubt other love, I wonder if maybe I’ve just been kidding myself about my interest in film.

Some months down my healing, I find an amulet in the shape of Abbas Kiarostami. Close-Up is the first film I watch, a revelation that subverts fiction, challenges documentary, makes me cry. Next, the Koker trilogy, a set of intertextual films set in rural Iran, starting with Where is the Friend’s House?, about a boy who has accidentally taken his schoolfriend’s notebook and must deliver it before the day ends. I watch this film without hitting pause or wanting to jerk myself away for a smoke.

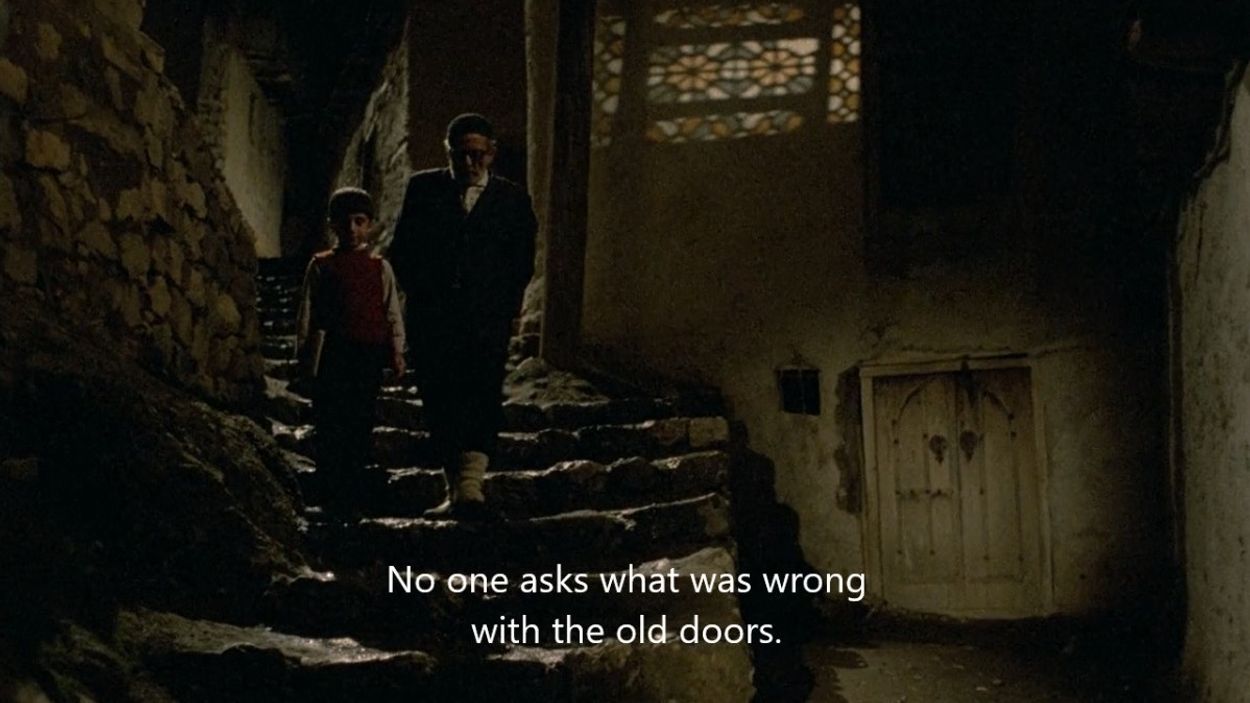

It is easy to sink into Kiarostami’s slowed down world, his ordinary people going about their lives, even in the backdrop of incredible trauma. Scenes are not rushed; characters enter, exit, re-enter and we’re still there. Dialogue is leisurely, no significant time jumps, plenty of still frames, long takes, sometimes too long for my friends’ liking. In Where is the Friend’s House?, a mother takes thirteen minutes to do laundry, first washing it then hanging each cloth one by one. Later, a boy leads an older woman outside, in glacial steps because she cannot walk and we see every second of their climb. Nature and landscape too, are not swiftly passing B-rolls or scene-setting devices, but characters given their due dialogue, their role in creating time: drives through the Koker landscape, long shots long of someone walking or running through the olive trees, always open air, trees, roads.

notes, june 2020

in fairytales a quest is meaningless without the journey there, the things you find unintended, the people you meet, the wandering - where is my friend’s house a fairytale - kid on notebook quest, the old doormaker the wizard leading the boy to his destination just when all hope is lost - except this a kiarostami film so destined to make your heart break - wizard turns out to have no wisdom after all, but is a wearied aged fallible man whose guidance fails so tremendously even the kid doesn’t have the heart to tell him - most magical sequence before that: their walk together, the child walking toward disappointment (disappointment is the wisdom), the ethereal windowframes - we would not have seen them had the child not wandered away - long scenes have potential for sudden magic to appear in the ordinary—

Most remarkable about Kiarostami films is their refusal to cut out the ordinary, the everyday: the walk with the wizard, a grandmother watering the plants, stopping along an errand to exchange Salaams with your neighbour. Nothing is too trivial for the camera, too undignified for the lens: every in-between conversation, routine encounter, off-track mundanity, planned or planned as it might be, as life is.

As life was: that I was unsettled in my heart, and the world unsettled cosmically by the pandemic, and in Kiarostami films I felt at home. A stillness, dwelling in the present, slowing down. Which is not to suggest that slowness is devoid of plot and drama, rather, that drama is inadvertently located in the ordinary, in nature, in quietude, if we pay attention and stay in the present long enough. Kiarostami gravitates the viewer through sound and silence so fiercely into the present as if to say: look, this is where tragedy and comedy spring from also, where everyday poetry is found: the flower lands up in a notebook, the surprise beauty of the tree with the birds, the glass windows sending patterned colours into the night though it’s too late now and the boy will miss the baker and his mother will be angry, still, there are the shadows from the glass windows if he looks up, the old door-maker walking alongside him, the magic in the mundane.

*

Our masterclass with Pedro Costa is the day after we watch Vitalina Varela, a looming epic of a film, though I couldn’t tell you what the plot was exactly. What I remember is getting lost in the shots, each a grand oil painting, sometimes movement so slow you could imagine the painter re-thinking strokes. I was interested whether Costa was influenced by paintings, whether they played a role in his visualisation. Particularly that shot when Vitalina is wearing a blue dress, standing in the kitchen. It reminded me powerfully of Vermeer’s Woman in a Blue Dress. Might it be a homage?

Costa is amused, smiles, and starts talking about postcards. That he enjoys postcards far more than paintings, and the room laughs. It wasn’t a direct homage to Vermeer, he clarifies, but then, says very seriously: “If you think about it … everything is a Vermeer. Look at the light there,” he points to the floor, the slanting Swiss sun, “That’s a Vermeer.” Sean half in shadow, “A vermeer.” The window. “A vermeer. Anything can be a Vermeer, you just have to look.”

Hamza Bangash is from my city, so this should be reasonable, but I’m not prepared for the opening shot of his short film, Stray Dogs Come Out at Night, premiering in Locarno Open Doors: a man walking down a Karachi street at night. That orange street-light; something inside me dislodges, how dissonant and thrilling to see what is home and habit to my eyes, as an elsewhere on-screen. Everyone in the hall is watching the same shots, but for them it is a foreign geography, their bodies do not pulse with the same recognition. It is surreal, this hit of relief and sinkage both, stemming from familiarity when all this while I have been training myself to look with new eyes. And it’s cliched, but it’s nice to see your city represented on-screen in the same festival which often categorizes Hamza’s films as Middle East and features maybe two South Asian movies in its entire line-up. That orange street-light, then. Is a different kind of magic, from a different kind of mundane.

*

One morning in Critics Academy, we meet with festival programmers. Before anything else we’re talking about the state of the world. The left’s failure, to be specific, the rise of fascism in the world, your country, my country, despair. Except for one programmer who, contrary our hopeless convictions, finds this time exciting. “Yes, the left is losing power,” she says, “But everything is shifting … and when all the pieces are up in the air, there’s movement … it means there’s room to re-arrange.” She continues: “The left was created by privileged people who have ideas of ‘good’ taste and ‘good’ politics. The left has to reinvent.”

And what does that look like? There’s one question that keeps coming up in our workshop: how do we honour historically excluded voices without tokenizing? That is, should diversification beyond lip service simply be a matter of quotas? Should we, for instance, include films by women by virtue of them being made by women alone? What about merit?

Her answer to this is something I keep going back to: that it is not a matter of numbers alone, but when numbers are skewed, we need to pay attention to what’s missing. Whose voices? And it is easy to reach then, for the nearest available film by the particular marginalised identity group, but that’s too easy. We have to dig deeper, not rush to fill quotas. Good films exist and always have, the hard work is looking for them. “Especially fragile films,” she says. “Films that don’t pretend to be bibles of the world.”

*

La Libertad by Lisandro Alonso is a simple, unembellished movie about a lumberjack, played by professional lumberjack Misael Saavdera, though he is never named. For ninety minutes we follow a day in his life. He wakes up, eats, defecates, goes to chop wood, has his lunch, listens to the radio, returns to work, sells wood, cooks dinner. Routine is the plot, and isolation the drama. The only people he interacts with are a guy at the gas station, and a wood-buyer. There isn’t anyone he really talks to, so whatever dialogue there is is between him and the axe, the radio, the stove.

Like Kiarostami films, the scenes in La Libertad are slow and long, linger on the mundane. There is only the mundane in Misael’s day; whether there is magic in it for him or not, we can only guess, but for the viewer: if you stay with it, the film becomes a kind of meditation. Misael’s body lifting and moving the tree trunks, his rhythmic to and fro to the axe’s dutiful strikes. The steel axe beating sound into the world, the trees answering, rustling, the birds harmonizing. Miseal eating a sandwich, patiently and methodically, listening to … a Spanish song? I do not understand the language but its hum comforts. And after a while I am strangely aware of my breath. I forget I am watching a film, I am in Misael’s world, hearing the rumble of the truck beneath him, touching the dog, and when I unforget, I hunger: the landscape is so close and so far, I want to touch it better, taste it more, I am aware of the distance. Then I forget again, and something peculiar happens. In movie frame, Misael has cut the trunks down and laid one of them on the forest ground, he is now slicing it with his axe, sharp horizontal hacks that remove its outer bark and reveal the soft brown underneath. In mind frame, I am in a trance, one with Misael’s monastic mission: transforming the rough tree trunk into a thin, smooth log, whittling away the darker bits… suddenly I am thinking of everything solved and unsolved in my heart.

notes, aug 2020: silence in film and fiction - silence being the place of observing (the charac looking out), of being observed (the lens on the charac) - silence from where springs surprise, the quiet where the world opens. at its root is lostness, of forgetting you are in the world / watching a movie … lostness leading to clarity - la libertad - freedom - a tree - a rock - a cloud - only in the mundane do the heart’s questions fully surface & are resolved - resolution is the surfacing - allowing them to roam, without consequence or action or - floating almost - films that let you travel, let your thoughts travel by anchoring you in the present, like a good walk, a cycle by the sea with a friend you see after four months.

*

When I forget I am watching a film, I feel one with the noise in my heart and head. It isn’t quietened or overbearing, but takes the form of a cloud-like sifting, floating through, and the film’s images become the air on which this noise travels. Annie Dillard says it better, except instead of a film, she talks about losing herself in a tree, and what happens when the charm is broken, the lostness lost: “...the second I become aware of myself at any of these activities - looking over my own shoulder, as it were - the tree vanishes … And time, which had flowed down into the tree bearing new revelations like floating leaves every moment, ceases. It dams, stills, stagnates.”

We have all found this feeling in nature, when gazing somewhere long enough. Similarly, scenes that stretch on longer can offer deeper excavations, wilder states, just by virtue of a longer gaze. Kiarostami says he wants viewers of his films to linger so they can choose what they see. When we linger (the to-and-fro movement of Misael’s body), we choose what we see (his shoulder-blades, how they shine in the sun), where we anchor our attention (the sun). And in this place of choosing, attention, stillness, our senses merge so mind can wander, and time bear new revelations like floating leaves... what surfaced for me, what heights wandered, is not important so much as the meandering itself, all the while gazing at Misael labouring, thinking about his troubles and joys too, the film a mirror through projection. A mirror to myself, not to confirm what I already know, but to open to what I had not noticed before. What I do not choose to look at, in myself, in the film. The sun on his shoulder-blades, I notice it on my second watch.

When he approached Misael Saavedra initially, Alonso recounts in an interview, Misael didn’t really know what to say. He had never been to a cinema in his life. Eight months later, Alonso was still in Argentina working on farms in La Pampa, when Misael came back and said OK, he was ready to make a film.

Genre-blurring films are exciting, not only because they leave us wondering what is life and what fiction, but because by working with non-actors, they do not pretend distance between life and cinema. Close-Up undertakes this in a hugely meta way, a film about a man who (in real life) impersonated another Iranian filmmaker. The film opens with Kiarostami meeting this man, in jail for fraud, and agreeing to make a film about his suffering. To make the film the imposter has to act, re-enact the scenes where he was already pretending to be someone else … what is life, what cinema, it’s brilliant. Many films pose the same questions without necessarily blurring the genre within the storyline, simply by hiring non-actors as leads. I think of Musa Saeed’s Valley of Saints set in Kashmir. I think of my friend Hamza’s latest short, 1978. Kiarostami, who largely works with non-actors, has a fantastic answer when asked about the difference between fiction and non-fiction. He goes off, doesn’t use those categories at all, instead, reflects on how films are not “created” but found, already there, their integrity and legitimacy anchored in the fact that something moved you, something touched you and you wanted to share it with someone.

As for Alonso, he says he just wasn’t paying attention in class when they discussed the difference between documentary and fiction.

*

I keep thinking about the title — La Libertad, which means freedom. What is Alonso suggesting freedom is? I’m thinking about this question in context of the pandemic, at a time when the ordinary is so sharply in focus, in its fragility and preciousness both, when the only thing in our control is our daily, and sometimes not even that. Misael is free in a way most of us are not, in a way most of us have been reminded we are not. His life is clocked to the forest’s. He dwells only in the present, each day’s timber and two meals. This is not where most of us live, but it is where we find ourselves thrust in times of utter defeat. When we are strung or charged, with anxiety, confusion, grief, whatever our specific monster, when anything faster than the clocks of our heart feels tiring. Exhausted already, it takes more than we have to pull ourselves and engage with the world. So my friends are having a lively time drinking and talking and I want desperately to be a part of it, but it’s all too much, and I check out, or leave. Or I watch Charlie’s Angels in the cinema but exit with no memory of it, what even happened, my heart was a mess and the movie a whirlpool. Then it is the mundane which saves me, saves us, in life and in film, the B-roll the site of relief, the precious moments of release and air allowing your gaze to relax, the slowed down moments that do not threaten to disrupt time, like watching your friend roll a joint or a tree shaking in soft wind or a long shot of a zig-zagging road the character takes several minutes to run through. The pandemic made us realise how little we know to stay still when the hurtling storylines vanish and there is just the present… in any case I was living my life in long takes, staring at the strip of sky between my building and the neighbours’, how steadily it lightens the paint on the walls. Or these days, listening intently to the South Asian monsoon, among those few gifts of nature you can trust will never stop giving, or taking. It is proving a useful skill in 2020, hacking time by staying in the present. As Dillard says, “The present is a freely given canvas. That it is constantly being ripped apart and washed downstream goes without saying; it is a canvas, nevertheless.” I am scared of too many cuts and leaps in time; they jerk me out of a world I am struggling to keep afoot in. I prefer slow films that ground me by directing my attention to the present, allow me to linger and choose what I see; they bring me to tears or happiness no differently than the monsoon raindrops and the sudden strip of pink sky: Misael’s hand touching the dog, Hussein’s face in Through The Olive Trees, he’s on the truck going to his shoot, not saying a word, quiet, inward, just thinking thinking feeling.

This essay is a defence, absolutely, of non-actors, of long takes and still frames, of privileging the mundane. With the entire world disrupted and forced to take stock, the past and future reels we cannot rely on, films like Alonso’s and Kiarostami’s feel crucial. My bias for slow films aside, perhaps these are the texts that can help us reflect on our own fragility by anchoring us fiercely in the world. (When I look it up, mundane is 19th century latin from mundus, “world”). They remind us that the mundane is the world, and like the world, does not lack drama and tragedy, comedy and magic. That films can be mimetic of life’s everyday surprise and softness, these fragile films that elevate the ordinary, render nothing unworthy of cinema, do not pretend to be bibles of the world, though perhaps they should. Anyway who can say what’s a bible for anyone, what is film, what life, where scripture.

*

A mundane / magical moment at Locarno last year: I am at the Kursaal. It is the first time in days that I have slotted time to spend with myself, drink coffee, smoke, and just journal. I am missing home, thinking about my partner, how I cannot wait to return and discuss these films with him. Linda, my roommate and friend, also in the Critics Academy, is sitting opposite me finishing a review. We never watch the same films but get along fabulously. Suddenly it starts raining. Linda stops her work too, because it’s beautiful: not sunset yet, so the rain is a colourful haze of taps, knocking against the Kursaal’s glass walls. Outside everything blurs, Locarno is wiped, just dots of red, yellow, green. I could be anywhere in the world, I think. Then enter a cinema and be elsewhere. And another, and another. What is this strange time out of time, time conquering time.

*

A mundane / magical moment at Locarno this year: I am in my room with my friend Noor. We have borrowed Natasha’s projector and set up our indoor cinema. The plan is to watch La Libertad, but Noor is under no compulsion to make it through the whole film, though she will. Somewhere in the middle, Misael is walking in the forest, the trees are swaying and we can hear the sounds of nature in the Pampas, the birds and the wind, when suddenly a car honks in my Karachi street below. For a moment the sounds coalesce: Misael’s ordinary on another continent merges with my ordinary, as if the honking is part of his world too, and he will walk out of the forest and get into a Mehran. It doesn’t seem so improbable, with the cosmic upheaval of this year, that these two mundanities for a moment become a single reality. The world can be so easily re-assembled. Or rearranged— you can rearrange the pieces when everything feels lost, remember?

You just have to linger.

And if you look long enough, everywhere’s a Vermeer.