By Christopher Small

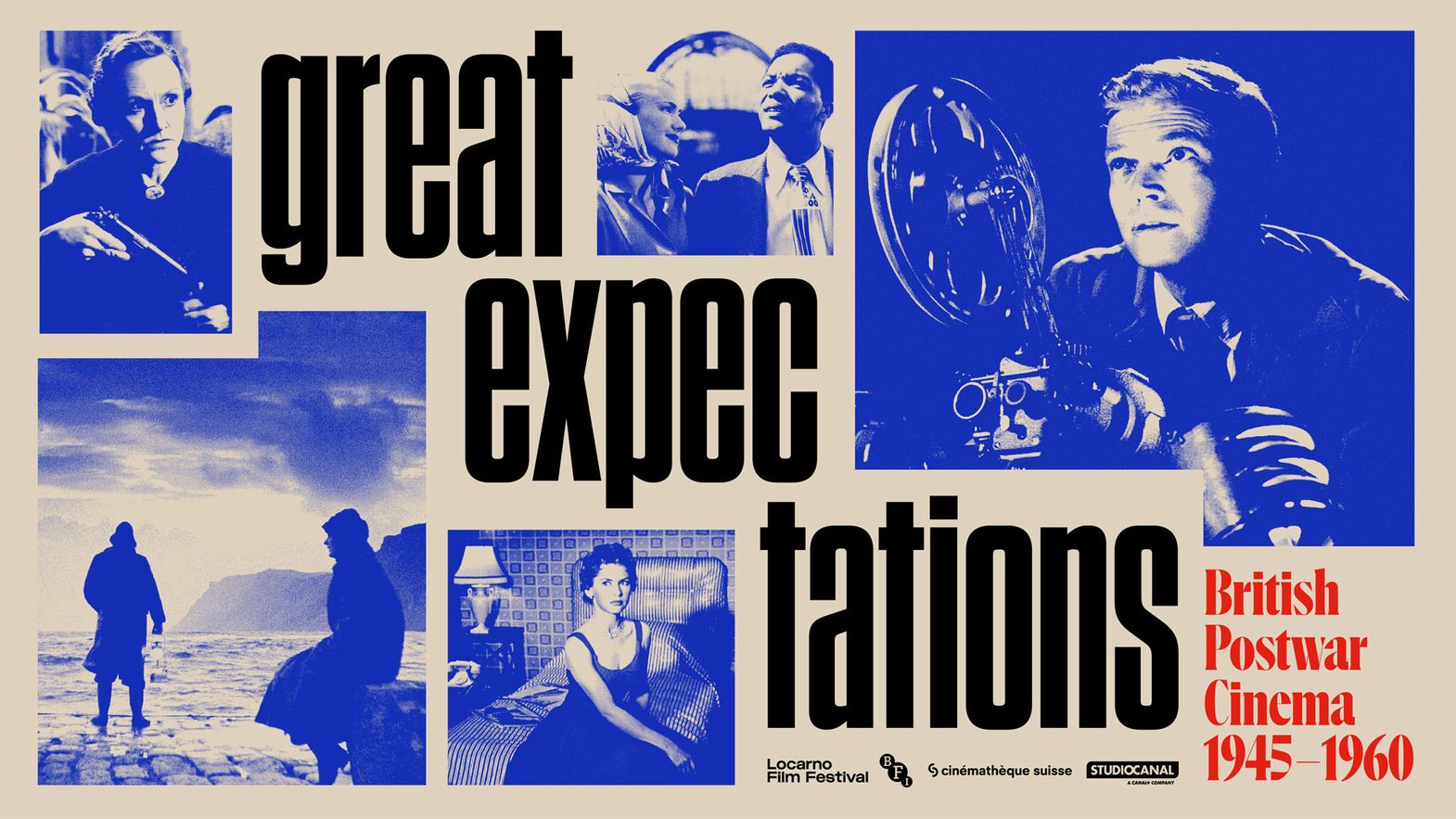

After a successful exploration of Columbia Pictures in 2024, curator Ehsan Khoshbakht once again will return to Locarno to craft the festival’s latest retrospective, this year focused on the postwar years of British cinema. For decades, British cinema of this era was looked at with condescension by auteurist-minded critics on the continent; of the figures of the French New Wave, François Truffaut was most memorably chauvinistic when he described the words “British cinema” as an oxymoron. Yet this snobbery was certainly not universal. In the US, for instance, prominent cinephile champions like Martin Scorsese continued to draw on the period for inspiration, long insisting on classical British cinema of the postwar years as an artistically fertile period ripe for rediscovery.

I spoke with Khoshbakht about the program, conceived as a focus on films about British life during the period of 1945-1960. Khoshbakht started his work with films made at the end of the Second World War and went, month by month, right up to Michael Powell’s once-critically reviled 1960 masterpiece Peeping Tom.

A Diary for Timothy (1945) by Humphrey Jennings. It is a remarkable film made during the final stages of World War II, with the knowledge that the war would soon end. Jennings asks, “What next?” We see a child being born: “What will happen to him?” “How can we make the world a better place for Timothy?” From there, I thought of doing a retrospective that explores what happened to that child in the years after that point, following his life and the lives of the people around him.

I grew up watching British films. Now, this is a very interesting point: we all know that Martin Scorsese discovered British cinema on television. This was because Hollywood studios were reluctant to sell the rights to television networks, so American channels filled their programming with British films. The same thing must have happened in Iran, where I was born and raised, because there was a very good collection of British films at the archive of National Television. After the revolution, when ties to the West were cut off, these were the only things remaining in the archive that they could still show. And they did show them on a regular basis. So, from the age of eight or nine, I discovered films by Harold French, Alexander Mackendrick, Ralph Thomas, and many others.

©Locarno Film Festival / Ti-Press

©Locarno Film Festival / Ti-Press

My research method was a primitive one: “Watch everything!” In any case, though it was made during and about the war, A Diary for Timothy contains no shots of war, combat, or the Blitz. We only hear about it in the soundtrack. I got the idea from there and thought to myself, “Don’t mention the war!” Yet, the Second World War – or its shadow – is present in almost every film in the program, all the way up to 1960. With that in mind, I thought this program should focus on the people of Britain as seen through British films, rather than the other way around. That’s why I came up with the idea of living day by day with the people, from September 1945 to December 1960, through British films made and set in the exact same period, hence the exclusion of films set in the past or future, or films with fantastical premises. This automatically meant focusing on the golden days of the British studio system. Even though the final years of this period overlap with the kitchen sink and New Wave movements, I thought that I shouldn’t mix the two. I wanted the attention to be on the unsung heroes of British cinema.

The two directors I didn’t know much about – beyond their names and a film or two – but who now rank highly in my mind, and who I consider significant figures, are Jack Lee and Gordon Parry. Revisiting the work of George King reminded me just how rich his mise-en-scène is. Daniel Birt’s collaborations with Dylan Thomas are fantastically dark and lyrical. And needless to say, I think Lance Comfort is one of the finest British directors ever. His Daughter of Darkness (1948) is closer to Mexican Buñuel than anything in British cinema.

Yes, British postwar cinema is unique with respect to the role women played in it. Women were equally invested in writing, directing, and producing genre works, particularly comedies and crime films. At the same time, they were making films that argued for a drastic redefinition of women's roles in post-war Britain, highlighting the enormous contributions women made during the war. Which is to say, if women could be so decisive in defending the country and winning a war against the Nazis, it would be absurd to think they couldn’t be equally effective in running society and taking on roles traditionally assigned to men. To Be a Woman (1951) by Jill Craigie is a wonderful short film that addresses this directly.

And you’re right, this openness in British cinema after the war also extended to figures who could no longer find work in Hollywood, by which I mean blacklisted or gray-listed Americans. What is astonishing is the speed with which those directors integrated into British cinema and tackled quintessentially British subjects, such as class (Joseph Losey), the psychological damage of the war (Edward Dmytryk), and mapping London cinematically as skillfully as did any British director (Jules Dassin). One shouldn’t forget that even before this post-1947 migration, there were many first-rate technicians in British cinema – mostly European Jews – who had fled their countries and contributed greatly to British films reaching their pinnacle of artistic and commercial success.

©1951 STUDIOCANAL FILMS Ltd

©1951 STUDIOCANAL FILMS Ltd

I do care about showing film on film. That’s always my priority, unless the alternative screening material, such as a restored DCP, is closer to the original look of the film and enhances the viewing experience. A great number of precious 35mm archive prints are coming straight from the BFI, the home of British cinema. However, other distributors are also contributing some fine prints to this program. There might even be a print or two coming from Hollywood studios, as some of these British films were financed by Hollywood, and they have the best elements available. Nearly 30 titles will be shown in analogue format, with the rest presented digitally. The majority of the digital copies are recent restorations and preservations.

Understanding the dark edge that British films have, contrary to common notions of the British character. Their self-criticism is sharp and pointed, and many of the questions they raise remain relevant to this day. Moreover, British cinema, alongside Italian cinema, had one of the most consistent and rewarding studio systems in Europe—one that remains largely unexplored. I hope this program opens peoples’ eyes to the brilliance, sheer visual exuberance, and great artistry of directors who deserve more recognition internationally and even nationally, considering how little has been done to celebrate them, even in Britain.